- Search Close search

- Find a journal

- Search calls for papers

- Journal Suggester

- Open access publishing

We’re here to help

Find guidance on Author Services

Free access

Defining “drinking culture”: A critical review of its meaning and connotation in social research on alcohol problems

- Cite this article

- https://doi.org/10.3109/09687637.2016.1153602

Introduction

Summary of the critique of the understanding of the drinking culture concept in alcohol research, making sense of different cultural entities and their interactions, conclusion: ways forward, acknowledgements.

- Full Article

- Figures & data

- Reprints & Permissions

- View PDF PDF

There has been growing academic interest in “drinking cultures” as targets of investigation and intervention, driven often by policy discourse about “changing the drinking culture”. In this article, we conduct a critical review of the alcohol research literature to examine how the concept of drinking culture has been understood and employed, particularly in work that views alcohol through a problem lens. Much of the alcohol research discussion on drinking culture has focussed on national drinking cultures in which the cultural entity of concern is the nation or society as a whole (macro-level). In this respect, there has been a comparative tradition concerned with categorising drinking cultures into typologies (e.g. “wet” and “dry” cultures). Although overtly focused on patterns of drinking and problems at the macro-level, this tradition also points to a multifaceted understanding of drinking cultures. Even though norms about drinking are not uniform within and across countries there has been relatively less focus in the alcohol research literature on cultural entities below the level of the culture as a whole (micro-level). We conclude by offering a working definition, which underscores the multidimensional and interactive nature of the drinking culture concept.

- drinking culture

- public health

Policy documents increasingly refer to the need to “change the drinking culture” as a way of addressing problems associated with alcohol use (Her Majesty’s Government, Citation 2012 ; Ministerial Council on Drug Strategy, Citation 2006 ; Victorian Government, Citation 2008 ). At least in part reflecting this, interest in drinking culture has also grown in academia. As indicated in Figure 1 , the number of academic journal articles in the health and social sciences that contain the term appears to have grown steadily since the early 2000s.

Figure 1. Journal articles in the SCOPUS database containing the term “drinking culture/s” between 1967 and 2014.

Although there is considerable anthropological and sociological literature on culture and drinking (e.g. see Douglas, Citation 1987 ; Heath, Citation 1987 ; Hunt & Baker, Citation 2001 ), the issue of cultural aspects of drinking has also come to the fore in public health-oriented research that is concerned with the description, prevention and alleviation of health and social problems. This is not surprising given that public health has traditionally focussed on social determinants of health and upstream factors beyond the level of the individual. However, in much social research on alcohol, public health’s traditional focus on environmental and structural factors has been relegated to the background in favour of a focus on the individual (and individual responsibility), behaviour change and unhealthy lifestyles, of which alcohol consumption is seen as a part (Hunt & Baker, Citation 2001 ).

In the public health-oriented literature on alcohol and other issues, there has been a tendency to treat “context” and causality in over-simplistic ways (Hart, Citation 2015 ; Shoveller et al., Citation 2015 ) and to discount the pleasures of alcohol use (Hunt & Baker, Citation 2001 ). Given this tendency for oversimplification, we undertake a critical review of public health-oriented alcohol research (henceforth referred to as “alcohol research”) to trace how this body of work has understood and deployed the concept of “drinking culture”. Consistent with the critical review approach, we aim to “go beyond mere description of identified articles” deploying the drinking culture concept and “offer a degree of analysis and conceptual innovation … to ‘take stock’ and evaluate what is of value from the previous body of work” (Grant & Booth, Citation 2009 , p. 93). We do not attempt an exhaustive inventory of all the available literature on alcohol and culture, nor even all the public health-oriented literature; our concern is primarily with “the conceptual contribution of each item of included literature”, and as such this article “may provide a ‘launch pad’ for a new phase of conceptual development and subsequent ‘testing’” (Grant & Booth, Citation 2009 , pp. 93, 97). In particular, we trace the application of the drinking culture concept to different cultural entities at both macro- and micro-levels, and in so doing examine points of consensus and departure in terms of how drinking cultures have been understood in alcohol research. We utilise insights from anthropological and sociological literature to draw attention to potential oversimplifications, limitations and ways forward for alcohol research. In so doing, we encourage a nuanced and multi-dimensional understanding of drinking cultures and provide insights into how drinking cultures might be defined, investigated and monitored.

We show that the alcohol research literature offers little in terms of explicitly defining what is meant by the term “drinking culture”. Even in a recent review of drinking cultures, Gordon, Heim, & MacAskill ( Citation 2012 , p. 4) stopped short of a definition, suggesting that “the question of what constitutes drinking cultures is somewhat abstract and open to interpretation”. This conceptual ambiguity has not stopped researchers from viewing drinking culture as a target of investigation or intervention. Indeed in the very next sentence, Gordon et al. go on to state that their paper identifies “key themes influencing drinking cultures” and reviews “their nature and function” (2012, p. 4). By skipping over any detailed conceptual discourse or discussion of how the study operationalises drinking culture, the concept is enacted paradoxically as commonsense and unproblematic – something that the reader intuitively understands.

On the contrary, we suggest that the widespread and unquestioned use of “drinking culture” terminology in problem-oriented alcohol research has deepened the ambiguity surrounding it and stifled conceptual development and understanding. We argue that alcohol researchers need to more clearly articulate what they mean when they refer to drinking cultures. Prior to making this argument, however, we begin with a brief overview of anthropological and sociological understandings of culture.

More than half a century after Kroeber and Kluckhohn ( Citation 1952 ) found 164 definitions of “culture” in the anthropological literature, Taras, Rowney and Steel ( Citation 2009 ) found it still true that “there is no commonly accepted definition of the word”. Taras et al. characterise culture as a “complex multilevel construct”, with shared assumptions and values as a core, and practices, symbols and artifacts as outer layers. They also emphasise stability – that a culture is shared by members of a group that it is formed over a long period, and that it is relatively stable. Jepperson and Swidler ( Citation 1994 ) suggest that for a particular cultural form, there is an underlying code of meaning and rules, there are “customs that have emerged governing it”, and there are “ideologies of talk surrounding it”.

In an exchange specifically concerned with alcohol and culture, Lemert ( Citation 1965 ) noted that in his fieldwork he had found that “group interaction and social control are far more significant than culture values in understanding of predicting … drinking” (p. 291). In reply, Mandelbaum ( Citation 1965 ) accepted this observation, adding that “I include under the term ‘culture’ those patterns of social control and of collective behaviour which are regularly used” (p. 292).

The exchange between Lemert and Mandelbaum set a pattern that has been a regular feature of discussions of alcohol and culture, emphasising social control aspects at least as much as shared values as central to the meaning of culture. Lemert ( Citation 1962 ) and Bruun ( Citation 1971 ) made strong contributions to this tradition in their typologies of cultures in terms of differences in characteristic means of controlling and minimising harm from drinking. We will discuss below the continuation of this tradition in analyses emphasising norms concerning drinking – prescriptive norms is the term in psychology – as building blocks of culture and drinking.

Drinking culture in a society as a whole

“tolerance (hence permissiveness to drinking), disapproval of ‘wowsers’ (hence the determination not to be a kill-joy oneself), the ideal of self-control and ‘moderation in all things’ (the main social control of drinking), conformity and belief in equality and stress on the adult male role (especially the pressure on adolescents to assume this role early)” (1968, p. 150).

“drinking as a symbol of mateship and social solidarity (especially in adult male drinking); drinking for social ease (particularly in home entertaining and cocktail parties); drinking as utilitarian (hence it is acceptable to use alcohol to ‘drown one’s sorrows’); excessive drinking as socially more acceptable as an outlet for deviance than, for example, delinquent acts or schizophrenia; drinking as virile behaviour; ‘holding one’s liquor’ as also virile; adults’ opinion that adolescent drinking should as far as possible be supervised; disapproval of heavy drinking and drunkenness in women” (1968, p. 150).

At the level of “general orientations”, many of Sargent’s generalisations are still recognisable, though much has changed in Australian society, including who does how much drinking where. However, in a complex multicultural society, there will be many subdivisions of the society where the generalisations do not apply. As Sargent intimates, the drinking culture of a society may refer and “belong” to some parts of the culture much more than to others. For instance, given the male predominance everywhere in heavier drinking, it has been remarked that what are referred to as national drinking cultures seem to mostly be referring to male drinking in the society (Gmel Room, Kuendig, & Kuntsche, Citation 2007 ). This is important to keep in mind as we discuss drinking culture at the level of the culture as a whole. It is also important to note that the distinction between macro- and micro-scales of focus should not be viewed as mutually exclusive or necessarily in conflict, but are perhaps best seen as complementary perspectives.

The typological tradition

Concern with drinking norms and functions at the macro-level is evident in many early discussions of culture and drinking, in which academics used examples of drinking in different societies to develop typologies of the position of alcohol in cultures (Room & Mäkelä, Citation 2000 ). These typologies are of interest because such classifications make differentiations on various dimensions. Examining the dimensions that are chosen provides insights into thinking around what is meant by a drinking culture.

A fuller catalogue of typologies identified in the literature can be found in Table 1 . Many of the typologies in Table 1 are focussed on drinking patterns and problems. We mention a few that are particularly noteworthy here.

Table 1. Typologies of drinking cultures identified in the literature.

A strict system of legal and organisational control of accessibility of alcohol seems to be related to low alcohol consumption, but also to a high degree of public nuisance. The causal chain probably goes like this: A drinking culture with a large degree of highly visible, non-beneficial effects of alcohol consumption leads to a strict system of control, which somewhat reduces total consumption, which again influences and most often reduces the visible problems. But also, the system of control influences the visible problems – sometimes probably in the direction of increasing them … . In determining the amount of consumption and the problems created by consumption, I do not perceive the system of control as the independent variable. I view the system of control to be inter-related with the amount of consumption and especially with visible problems (Christie, Citation 1965 , p. 107).

Despite being critiqued from a number of angles (see Gordon et al., Citation 2012 ; Room & Mäkelä, Citation 2000 ), the wet–dry typology had the virtue of being one of the first to highlight systems of social controls as an important feature of drinking cultures, an aspect to which we will return.

Open and airy wine shops in Mediterranean cultures, with drinkers sitting in small groups around tables.

The huge darkened beer halls of Germany and Austria, with long parallel tables flanked by benches.

The stand-up bar of English pubs, with drinkers standing in a line.

What is most striking about this typology is not just the focus on places in which drinking might typically occur (e.g. a beer hall, wine shop, bar, etc.), but the detailed attention to how the drinking space feels, how it is organised in relation to the drinker and how drinkers relate to other drinkers. This relatively nuanced rendering of setting foregrounds a complex web of interactions that may occur between spatial arrangements and activities in drinking environments, individual drinkers, the drinking group and others in the drinking environment. Also of note is the absence of any mention of drinking behaviour, problems or drunkenness, which is a departure from most other typologies (d'Abbs, Citation 2014 ).

Alcohol intoxication isolated into a sacral corner (e.g. orthodox Jews).

Alcohol intoxication confined to clearly demarcated occasions (e.g. the Camba in Bolivia).

The Scandinavian model: vacillation between “Dionysian acceptance and ascetic condemnation of drunkenness”.

As in thinking on the wet–dry typology, social control of alcohol emerges as a key feature of drinking culture in Mäkelä’s ( Citation 1983 ) discussion.

“A common pattern, well suited to the affluence and opportunity of the industrialised workweek, is a couple of drinks every evening, just enough to feel some effects, and a drunken “blast” on the weekend” (Room & Mäkelä, Citation 2000 , p. 481).

Use-values (e.g. alcohol as nutrient, alcohol as an intoxicant, etc. (Mäkelä, Citation 1983 )).

Expectations about behaviours while drinking or intoxicated.

The cultural position of the drinker, the drinking group and the drinking occasion.

Modes of social control of drinking.

The nature of drinking-related problems and their handling.

These additional features, together with the basic features of the regularity of drinking and the extent of drunkenness, offer a range of dimensions on which a particular cultural entity can be characterised and measured.

“… homogenisation of lifestyles, urbanisation, greater female independence, globalisation of alcohol marketing (especially for beer, spirits and new beverages), and moves toward greater homogeneity of legislation and regulation (e.g., EU [European Union] alcohol policies)” (Gordon et al., Citation 2012 , p. 8).

In this light it is worth considering how globalisation has affected what have been traditionally thought of as national drinking cultures. With increased flows of people, products, information and ideas across national borders, is it possible to conceive of a national drinking culture that sits in isolation from the “global”? For instance, marketing of alcohol by multinational producers may generate flows of images and messages that are shared globally via the internet and social media (Room, Citation 2010 ). Furthermore, scholars have noted a convergence of drinking patterns between men and women living in the USA (White et al., Citation 2015 ) and in European countries (Beccaria & Guidoni, Citation 2002 ; Leifman, Citation 2001 ; Room & Mäkelä, Citation 2000 ), and trends around young people drinking less have been described in various countries (de Looze et al., Citation 2015 ; Pennay, Livingston, & MacLean, Citation 2015 ). The analysis by Gordon et al. ( Citation 2012 ) prompts us to think about the extent to which phenomena of globalisation may be implicated in these recent observations (see Leifman, Citation 2001 ; Room, Citation 2010 ).

In what seems like a jump in their argument, Gordon et al. ( Citation 2012 ) also argue that the regularity of drinking and the extent of drunkenness dimensions proposed by Room and Mäkelä ( Citation 2000 ) could be encapsulated by a single “hedonism” dimension. They suggest that a hedonism dimension could also capture the extent to which individuals’ general lifestyles with regards to alcohol can, for example, be described as hedonistic (or ascetic).

Proposing a single dimension to characterise a culture’s drinking style, with “ascetic” at one end of it, seems reminiscent of old temperance-movement framings, with an implicit assumption that drinking will lead to intoxication. The dimension’s label assumes that both drinking and drunkenness are inherently hedonistic and thus opposed to dominant social discourses of restraint and moderation (Hunt & Barker, Citation 2001 ); but alcohol’s use-values are not limited to pleasure. Alongside their “hedonism” dimension, Gordon et al. ( Citation 2012 ) propose two other dimensions to characterise “drinking cultures”: function (“inter/intrapersonal, ritual, intoxication”) and modes of social control. But the presentation of their typology does not go beyond these minimal characterisations, and the authors make no attempt to classify any societies on the dimensions.

The numerous instances where Room and Mäkelä ( Citation 2000 ) point to exceptions to general correlational patterns highlight the difficulty of pigeonholing national drinking cultures into discrete categories. For instance, drinking in Mediterranean or wine-drinking cultures is strongly associated with meals, and is associated with “less officially recognised social disruption than elsewhere” (2000, p. 478). However, the notion of this seemingly idyllic kind of drinking culture (or a singular homogeneous culture) is rendered problematic in light of other literature, for example, about men drinking in the tavernas of Greece rather than in the home (Gefou-Madianou, Citation 1992 ), or about drunkenness that also occurs among young people in wine drinking cultures (Beccaria & Guidoni, Citation 2002 ), even if to a lesser extent. What this suggests is that at a societal level drinking cultures are not homogeneous. For the society as a whole, there may be recognisable characteristics that differ from patterns elsewhere – as in Sargent’s ( Citation 1968 ) characterisation of Australian drinking culture quoted above – but there are often also divergent features in subcultures or social groups, and often also in culturally defined “time out” periods.

Although we can point to flaws in each individual typology and in the way in which typologies are developed, the typological literature produces some useful insights. First, as the more nuanced typologies suggest, the drinking culture concept is not just about patterns of drinking (e.g. rates of alcohol use, types of beverages consumed) or problems (e.g. extent of drunkenness, alcohol-related mortality or morbidity) that exist in a cultural entity, but also encompasses meanings and use-values, the settings and places in which drinking occurs, and how drinking is controlled or regulated within a society.

Normative perspectives

A perspective which encompasses both the aspect of customs and expectations about drinking and the aspect of social control and adverse responses to drinking behaviour is the concept of norms. Room ( Citation 1975 ) argued that norms are the crucial building blocks lying behind the consumption patterns that had been the primary focus of previous discussions. Defining a norm as “a cultural rule or understanding affecting behaviour, which is to a greater or lesser degree enforced by sanctions” (1975, p. 359), Room notes that a norm is cultural in the sense that it is “not a property of an individual or a private understanding between people interacting with one another, but is a relatively permanent rule shared by a class of individuals who may not ever have met each other” (1975, pp. 359–360). In this respect a norm can apply at the level of the whole culture, a well-defined subculture or a less well-defined “social world” of persons with common interests or status. In Room’s usage, a norm can be an understanding held in common by “a group of people about what is appropriate behaviour” (1975, p. 359), but it can also take the form of a law or official regulation. Including formal rules as a kind of norms potentially brings the tools of government into the fold of drinking cultures (e.g. regulation, policy, etc.).

The typological tradition’s emphasis on social control as a dimension of drinking cultures is reflected in Room’s ( Citation 1975 ) allusion to “sanctions”, which he suggests can be formal and severe (e.g. a fine, getting thrown out of a bar, being arrested and charged, etc.) or can be informal and transitory (e.g. a lifted eyebrow, a disapproving look, etc.). However, norms can act not only as mechanisms to limit behaviour, but also to encourage particular behaviours (e.g. norms about buying rounds of drinks). In contrast to the focus on “drinking” behaviour and patterns in the typological work, Room highlights that most norms are directed at behaviour during or after drinking.

A major point that Room ( Citation 1975 ) makes is that norms governing drinking and associated behaviour differ “both according to the social situation – time and place and occasion – and according to the individual status on various social differentiations” (p. 361). Examples of norms include the appropriate age to be a drinker, situations in which it is appropriate to drink (e.g. not at work), traditional expectations about women drinking less than men or older people drinking less than young people. Although drinking cultures have often been depicted implicitly as aggregates of individual actions carried out in certain prescribed ways (e.g. in wine-drinking cultures there will be less drunkenness, in dry countries there will be more drunkenness, etc.), Room directs our attention to the social, relational and emergent qualities of drinking behaviour and drinking problems, arguing that these “arise out of the interaction between the drinker’s behaviour and the various responses of others” (1975, p. 360).

Dimensions of focus in studies of drinking cultures at a macro-level

In order to obtain an indication of the dimensions of drinking culture alcohol researchers have focused on recently, we identified peer-reviewed articles in health and social science journals that included the term “drinking culture” between 2010 and 2015. This illustrated that the way in which drinking cultures have been researched at the level of the culture as a whole (the macro-level) has been similar, irrespective of the tradition in which the study might be located. Change over time analyses and cross-national comparisons have predominated. As illustrated in Table 2 , most studies tend to be quantitative, with many drawing on general population survey data.

Table 2. Recent studies on drinking culture at a macro-level, 2010–2015.

As can be seen in Table 2 , studies tend to focus on a limited number of dimensions of drinking culture. In studies examining drinking patterns, a focus on intoxication and alcohol-related problems is common (e.g. Härkönen, Törrönen, Mustonen, & Mäkelä, Citation 2013 ; Loughran, Citation 2010 ; Mäkelä, Tigerstedt, & Mustonen, Citation 2012 ; Mustonen, Mäkelä, & Lintonen, Citation 2014 ; Raitosalo et al., Citation 2011 ; Stickley, Jukkala, & Norstrom, Citation 2011 ). For instance, in their study of changes to Finnish drinking culture between 1968 and 2008 using general population survey data, Mäkelä et al. ( Citation 2012 ) note that Finland has become a “wet” drinking culture, although sporadic intoxication (primarily on weekends and evenings) still maintains an important role of the drinking culture. Many of the studies focus on young people (e.g. Beccaria & Prina, Citation 2010 ; Bye & Rossow, Citation 2010 ; Hellman & Rolando, Citation 2013 ; Loughran, Citation 2010 ; Petrilli et al., Citation 2014 ; Rolando, Citation 2014 ; Rolando, Beccaria, Tigerstedt, & Törrönen, Citation 2012 ), reflecting a conceptualisation of youth drinking as in itself a problem, and ignoring the range of other frames in which the material might be analysed. In addition, with the exception of a few studies (e.g. Härkönen et al., Citation 2013 ; Mäkelä et al., Citation 2012 ; Mustonen et al., Citation 2014 ; Raitasalo et al., Citation 2011 ), the role of place, occasions and the settings in which drinking occurs has been largely neglected in recent alcohol research. Similarly, use-values and modes of social control have been understudied.

The dominant research interest in problem-focussed dimensions of drinking culture at a macro-level might be seen as reflecting a public policy discourse about drinking culture, in which changing the drinking culture is viewed as a way of preventing and minimising harms (e.g. Victorian Government, Citation 2008 ), often presented as an alternative solution to social problems that do not require government interference in the market.

A drawback of focussing on a limited number of dimensions of drinking culture at a macro-level is that we are unable to understand how these dimensions interact in different circumstances and apply to different population groups. This may lead to an overly simplistic understanding of drinking culture as acting in predictable ways, with predictable effects, irrespective of the other forces that may be operating in any given drinking situation.

It should also be noted that the majority of studies of drinking culture at the macro-level focus on European countries, with Finland and Italy being particularly prominent. Given observations of shifting drinking patterns in Finland and Italy (e.g. Allamani & Prini, Citation 2007 ; Mäkelä et al., Citation 2012 ), it is understandable that researchers would be interested in why these changes have occurred. The applicability of findings on drinking culture from Europe to other countries is unclear.

As we have illustrated thus far, there are a number of limitations in the way “drinking culture” has been understood and studied in alcohol research, and thus good reason to consider potentially novel ways of conceptualising drinking cultures. There is a well-established anthropological and sociological criticism of alcohol research understandings of drinking culture highlighted thus far (see Douglas, Citation 1987 ; Heath, Citation 1987 ; Hunt & Baker, Citation 2001 ). This has been most recently summarised by d’Abbs ( Citation 2014 ), who, like Room and Mäkelä ( Citation 2000 ), argues for a more nuanced understanding of drinking cultures, making three key points.

First, the emphasis on problems associated with drinking patterns and intoxication in discussions around drinking culture has obscured some of the meanings and practices associated with alcohol use that are culturally significant. As we have suggested, much of the research discussed on drinking cultures can be situated within a public health discourse, which views particular levels of alcohol use as “risky” and “harmful” irrespective of the context and purposes of use. As such, “drinking culture” as a determinant or mediator of alcohol use is viewed as a target for monitoring and intervention. The problem with this discourse is that it oversimplifies drinking cultures and does not take into account the benefits that alcohol use may confer (e.g. pleasure, social connection, intimacy, cultural belonging, cultural capital, etc.) and the way it is used in cultural practices (e.g. celebrations, religious occasions, etc.). Indeed there is a considerable body of sociological and anthropological work in particular that argues for the need to include pleasure in analyses of individual and collective decision-making about using alcohol and other drugs (e.g. Bancroft, Zimpfer, Murray, & Karels, Citation 2014 ; Bunton, Citation 2011 ; Duff, Citation 2008 ; Moore & Measham, Citation 2012 ; O'Malley & Valverde, Citation 2004 ; Ritter, Citation 2014 ). Without appreciation of the pleasure of alcohol use and other factors, attempts to change drinking cultures are likely to be unsuccessful.

Second, d’Abbs ( Citation 2014 ) notes that there is a tendency for the literature around drinking culture to enact drinking culture as “a stable sociological entity, anchored to a delimited geographical or social space” (p. 4). But in general thinking about cultures, this is increasingly seen as a problematic view, with cultures coming to be seen rather “as networks of meanings that are continuously being renegotiated and reconstituted rather than transmitted” (Hannerz, Citation 1992 cited in d'Abbs, Citation 2014 , p. 4). In this context, d’Abbs ( Citation 2014 ) urges us to move away from viewing drinking culture as a static entity with prescriptive norms that are “linked to sanctions and rewards designed to foster conformity and discourage deviance” (p. 4). Drinking cultures do not necessarily produce consistent and predictable behaviour, independent of the other contextual forces in which they are entangled in a given situation. Rather, there is a need to examine how drinking culture manifests in relation to other actors, use-values, practices and settings, in a given local situation. This necessitates the need for a shift in examining drinking cultures from the macro to the micro.

Third, there is another good reason for this shift, as d’Abbs ( Citation 2014 ) notes. The notion of a national drinking culture assumes that the nation is a homogeneous entity. But patterns of, and norms about, drinking as with other social behaviours, are not uniform within a single country (Fortin, Bélanger, & Moulin, Citation 2015 ). In fact, there are often great variations, which in part reflect variations in norms about drinking between different subgroups in the population. As d’Abbs ( Citation 2014 ) argues, there may be many drinking cultures within a society, necessitating a micro-level focus, below the level of the culture as a whole. We will draw on such insights in understanding drinking culture from anthropology and sociology later when we propose a working definition.

Below the culture as a whole

“Subcultures” (e.g. Hall & Jefferson, Citation 1976 ), “contracultures” (or “countercultures”; e.g. Yinger, Citation 1960 ), “subworlds”, “social worlds” (e.g. Unruh, Citation 1980 ), “scenes” (e.g. Moore, Citation 2004 ; Straw, Citation 1991 ), and “neo-tribes” (e.g. Bennett, Citation 1999 ) are among the array of terms used to describe cultural entities below the level of the culture as a whole, with each term offering a different meaning and frame of reference for “sub-entities”. In general, “subculture” (and related terms such as “contraculture” or “counterculture”) are used to refer to relatively holistic cultural entities that engross a good deal of members’ lives and times and which often provide a master identity for members. Terms like “social worlds” or “scenes” tend to indicate cultural entities more limited in their claim on participants’ lives, often referring to situations where members participate in several different “worlds” or “scenes”, and move back and forth between them as a matter of course. It should be recognised that there is no clear agreement on terminology or how best to operationalise cultural entities in terms of understanding their uniqueness, fluidity, degree of completeness or influence.

Despite the lack of agreement around terminology, sub-societal cultural groupings (e.g. subcultures, social worlds, scenes) tend to be both objects of self-conscious identification by members, and to be recognised and assigned a group identity from members of the larger society. The distinctions in norms between the cultural group and the larger society are often recognised by those outside the grouping, and are always recognised by those on the inside. For some sub-societal cultural entities, membership is considerably bounded by stable and largely assigned characteristics of the individual such as ethnicity, social class or geographic residence – ethnic subcultures or occupational subcultures, for instance. On the other hand, there are subcultures or social worlds where becoming a member is to a considerable extent a matter of choice and style – cultural entities such as rap or house music aficionados, graffiti artists, skateboarders or athletic “jocks”, to cite some social worlds which have been studied (e.g. Bennett, Citation 1999 ; Eckert, Citation 1989 ; Thornton, Citation 1995 ; Hall & Jefferson, Citation 1976 ). However, “choice” and “assigned characteristics” are often both involved: for instance in their fieldwork interviews with young people in the UK, McCulloch et al. ( Citation 2006 , p. 539) show how “young people’s subcultural styles and identities are closely bound up with social class”, which is largely assigned. In any case, rules about drinking and associated behaviour – including norms about limiting drinking or not drinking – are often a part of the normative structure of the subculture or social world, whether the entity is defined in terms of assigned characteristics or in terms of members’ shared interests.

In the field of ethnography, the cultural entity – the scene, social world, or subculture – is studied through particular sets of people in regular interaction with other as they act out their group participation. To qualify as a cultural entity, it can be argued that the group’s norms and practices must extend beyond a particular face-to-face group, so that even members of the grouping who have not met each other will be able to recognise a common set of norms.

There are various examples of face-to-face groups operating between social worlds or scenes (for example see: Chatterton & Hollands, Citation 2003 ; Grace, Moore, & Northcote, Citation 2009 ; Jayne, Holloway, & Valentine, Citation 2006 ; Measham & Brain, Citation 2005 ; Roberts, Citation 2015 ; Pennay, Beccaria, Prina, & Rolando, Citation 2012 ; Valentine, Holloway, Knell, & Jayne, Citation 2008 ; Winlow & Hall, Citation 2006 ), and of the way in which these worlds have their own style of communication and set of activities although these studies do not usually adopt a problem perspective.

This previous research has highlighted among other things the fluid nature of scenes, with individuals moving between different groups and changing their alcohol and substance use practices accordingly. It has also highlighted the different norms and drinking practices that operate across groups, settings and gender. This is also a point that Hutton, Wright and Saunders ( Citation 2013 ) make in relation to young women’s drinking cultures in New Zealand, albeit in terms of identifying risky and pleasurable places in order to inform harm reduction interventions.

“Cultures and cultural quantities like ethnicity are created anew as much as they are inherited from the past. Thus, for immigrants from Latin America, attitudes towards drinking and actual drinking behaviour do not simply reflect what people ‘left behind’ versus what they ‘find’ (and ‘move toward’) in the United States. Ethnic identity can also intensify following migration, and as part of this process alcohol use and abuse can undoubtedly change” (Gutmann, Citation 1999 , p. 182).

Often, indeed, the drinking behaviour of an ethnic group in a multicultural environment can be interpreted as an element in a performance before other elements of the society (Room, Citation 2005 ; Stivers, Citation 1976 ). What is evident in these examples is that each scene or social world has different norms, customs, sanctions and use-values associated with alcohol, and these often differ from those identified in macro-level typologies of drinking culture.

Cultural entities, whether at the whole-culture level or as subordinate groupings, should not be assumed to be unchanging and unchangeable, nor are they necessarily in conflict. With this in mind, we propose it is important to consider what the layers of influence are surrounding multiple entities and the culture as a whole and whether there is a hierarchy. Questions such as this must be considered as we untangle and make sense of complex social and cultural arrangements.

To better understand the way in which drinking cultures operate it is important to understand how subcultures or social worlds interact with the larger culture. This is a common topic in studies of contracultures, but is often neglected in studies of more integrated cultural entities. Room ( Citation 1976 ) argues that there is a loose social world of heavy drinkers in complex societies like the USA or Australia. Members of this world share an understanding of a set of norms that support and require heavy drinking in particular situations – for instance, norms about drinking etiquette and buying rounds in a pub or club. These norms may vary from the norms of the general culture, but heavy drinkers and the general population co-exist relatively peacefully. The means through which the social world of drinkers co-exists with the general population norms is through what Room calls “an implicit compromise policy of enclaving”. Enclaving the social world of heavy drinking is “an agreement that the world … will be tolerated so long as it conducts itself only within certain boundaries” (1976, p. 363). This agreement needs to be maintained by both sides (e.g. bars and their patrons keep what goes on inside the bar from being too visible to others, etc.).

Sequence problems or problems of transition – where we find ourselves intoxicated in a situation where it is no longer appropriate (e.g. wrong place at the wrong time). For instance, this can occur when a bar closes and an intoxicated person finds themselves in the street or the partygoer finds herself or himself responsible for driving home. This can be solved by changing the normative structure of one or other of the sequenced situations or allowing more time between the two situations.

Boundary problems – in which the boundary of the zone in which heavy drinking is normative is breached either accidentally or deliberately by those “outside” or “inside” the boundary. The agreement of accommodation implied by enclaving becomes unstable, and people in the social world of heavy drinking may try to extend its reach whereas those in the general culture (e.g. moral entrepreneurs, law and order advocates or public health advocates), may seek to hem the social world in (e.g. contests around public drinking). Boundary problems can be resolved through strengthening the insulation surrounding the enclaves, as well as changing the normative structures on one side (e.g. smoking outside if people object to smoking indoors, etc.).

Room notes that, although efforts to control heavy drinking social worlds may reduce consumption, they may also sometimes increase the visibility of drinking-related problems, which in turn can result in resistance from members of the social worlds under observation. The concepts of “enclaving”, “sequence problems” and “boundary problems” provide useful ways of thinking about the way in which micro- and macro-level drinking cultures may interact, and how conflicts over drinking norms might be resolved.

As we have articulated throughout, much of the alcohol research on drinking cultures has focussed narrowly on alcohol consumption and alcohol problems, obscuring the multidimensional nature of drinking cultures. This has essentially isolated alcohol consumption and problems from the network of other possible interactional and cultural factors involved. However, as Duff notes, research needs to focus on the way in which alcohol consumption “is enacted, performed or ‘entrained’ within a wider network of social, material and affective forces” (Duff, Citation 2013 , p. 267) in different occasions. Similarly, we have identified a need to acknowledge the multiplicity of “drinking cultures” at different scales (macro and micro) and the way that these might interact and be configured in different circumstances.

Drinking cultures are generally described in terms of the norms around patterns, practices, use-values, settings and occasions in relation to alcohol and alcohol problems that operate and are enforced (to varying degrees) in a society (macro-level) or in a subgroup within society (micro-level). Drinking culture also refers to the modes of social control that are employed to enforce norms and practices. Drinking culture may refer to the aspects concerned with drinking of a cultural entity primarily defined in terms of other aspects, or may refer to a cultural entity primarily defined around drinking. Drinking cultures are not homogeneous or static but are multiple and moving. As part of a network of other interacting factors (e.g. gender, age, social class, social networks, individual factors, masculinity, policy, marketing, global forces, place, etc.), drinking culture is thought to influence when, where, why and how people drink, how much they drink, their expectations about the effects of different amounts of alcohol, and the behaviours they engage in before, during and after drinking. The degree and nature of the influence that drinking cultures have on individuals is not inevitable but will depend on the configuration of factors in play in any given situation, and the nature of the relationships between the culture as a whole and smaller cultural entities as they affect the individual.

We acknowledge that attempting to define “drinking cultures” is a potentially fraught exercise and that there is other sociological and anthropological work that would be useful in the conceptualisation of drinking cultures, but we offer this “working definition” as a way of stimulating further conceptual thought and discussion amongst alcohol researchers and others. We also propose this working definition as a first step in thinking about how alcohol researchers might study drinking cultures in their complexity and possible questions such studies might pose. For instance, our definition foregrounds multiple dimensions that researchers might investigate, including norms about who can drink, patterns (how frequently and how much is it acceptable to drink?), practices (what is acceptable/unacceptable practice and behaviour during and after drinking?), alcohol problems (what constitutes an alcohol-related problem and how should such a problem be handled?), settings (where is it appropriate to drink and where is it not? How are drinking spaces configured/inhabited? How should people move between spaces/places when they are drinking or have finished drinking?), occasions and times (when is it acceptable to drink or get drunk?), use-values (what does alcohol use mean? What purpose does it serve?), and modes of social control (what are the informal and formal sanctions that are in place when norms are breached?). We acknowledge that anthropologists and sociologists readily ask many of these questions, and that alcohol researchers are already asking some of these questions or are attending to one dimension of drinking culture or another. However, we suggest that it would be valuable for alcohol researchers to attend to these simultaneously if we are to investigate drinking cultures in their complexity.

As our definition attends to the multi-dimensional nature of drinking cultures and their interactions, researchers might also explore how micro- and macro-level drinking cultures relate, and how drinking culture acts in combination with a range of other factors to produce effects. For instance, we might ask what influence does drinking culture have in different circumstances, occasions, settings and groups, and why is it more or less influential in particular circumstances than others? Addressing these questions may more productively inform attempts at changing drinking cultures.

Policy makers have increasingly argued that there is a need to “change the drinking culture”, and have sought to understand the drivers or impacts of changes in the drinking culture. But, given the conceptual ambiguity surrounding the concept, it is unclear what exactly needs to be changed. This article represents an attempt to conceptualise drinking cultures with reference to the relevant alcohol research literature and in light of insights from broader sociological and anthropological work. In so doing we have highlighted the multiple and multifaceted nature of drinking cultures at both macro- and micro-levels. Engaging with such conceptual complexities will hopefully sharpen attempts at investigating and changing drinking cultures. However, further empirical work in diverse contexts is needed to better understand drinking cultures, their interactions and their entanglement with other factors. Given that the majority of alcohol research discussed focuses on drinking cultures in European and Anglophone countries, there is a particular need for research outside these countries. Furthermore, additional work is necessary to examine policy makers’ understandings of drinking culture and how these compare with academic and “lay” definitions of drinking cultures.

We would like to thank VicHealth for funding the project that was the basis for this paper. In particular, we would like to thank Emma Saleeba and Sean O’Rourke for their helpful feedback throughout the project.

Declaration of interest

M.L. and A.P. are supported by NHMRC Early Career Fellowships (1053029 and 1069907, respectively). This work was supported by a contract from the Victorian Health Promotion Foundation (VicHealth) and by a grant from the Foundation for Alcohol Research and Education (FARE).

- Ahlström-Laakso, S. (1976). European drinking habits: A review of research and some suggestions for conceptual integration of findings. In Everett, M., Waddell, J., & Heath, D. (Eds.), Cross-cultural approaches to the study of alcohol. An interdisciplinary perspective (pp. 119–132). The Hague and Paris: Mouton Google Scholar

- Allamani, A., & Prini, F. (2007). Why the decrease in consumption of beverages in Italy between the 1970s and the 2000s? Shedding light on an Italian mystery. Contemporary Drug Problems , 34 , 187–197. doi: 10.1177/009145090703400203 Google Scholar

- Allamani, A., Voller, F., Pepe, P., Baccini, M., Massini, G., & Cipriani, F. (2014). Italy between drinking culture and control policies for alcoholic beverages. Substance Use and Misuse , 49 , 1646–1664. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2014.913386 PubMed Web of Science ® Google Scholar

- Bales, R.F. (1946). Cultural differences in rates of alcoholism. Quarterly Journal of Studies on Alcohol , 6, 480–499 PubMed Google Scholar

- Bancroft, A., Zimpfer, M.J., Murray, O., & Karels, M. (2014). Working at pleasure in young women’s alcohol consumption: A participatory visual ethnography. Sociological Research Online , 19 , 20. doi: 10.5153/sro.3409 Web of Science ® Google Scholar

- Beccaria, F., & Guidoni, O.V. (2002). Young people in a wet culture: Functions and patterns of drinking. Contemporary Drug Problems , 29 , 305–336. doi: 10.1177/009145090202900205 Google Scholar

- Beccaria, F., & Prina, F. (2010). Young people and alcohol in Italy: An evolving relationship. Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy , 17 , 99–112. doi: 10.3109/09687630802291703 Web of Science ® Google Scholar

- Bennett, A. (1999). Subcultures or neo-tribes? Re-thinking the relationship between youth, style and musical taste. Sociology , 33 , 599–617. doi: 10.1177/S0038038599000371 Google Scholar

- Bunton, R. (2011). Permissable pleasures and alcohol consumption. In Bell, K., McNaughton, D., & Salmon, A. (Eds.), Alcohol, tobacco and obesity: Morality, mortality and the new public health (pp. 93–106). Abingdon: Routledge Google Scholar

- Bruun, K. (1971). Implications of legislation relating to alcoholism and drug dependence. In Kiloh, L.G., & Bell, D.S. (Eds.), Proceedings, 19th International Congress on Alcoholism and Drug Dependence (pp. 175–181). Australia: Butterworths Google Scholar

- Bye, E.K., & Rossow, I. (2010). The impact of drinking pattern on alcohol-related violence among adolescents: An international comparative analysis. Drug and Alcohol Review , 29 , 131–137. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2009.00117.x PubMed Web of Science ® Google Scholar

- Chatterton, P., & Hollands, R. (2003). Urban nightscapes: Youth cultures, pleasure spaces and corporate power . London: Routledge Google Scholar

- Christie, N. (1965). Scandinavian experience in legislation and control. In Boston University (Ed.), National Conference on Legal Issues in Alcoholism and Alcohol Usage (pp. 101–122). Boston: Boston University Law-Medicine Institute Google Scholar

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1968). A cross-cultural comparison of some structural characteristics of group drinking. Human Development , 11 , 201–216. doi: 10.1159/000270607 PubMed Web of Science ® Google Scholar

- d'Abbs, P. (2014). Reform and resistance: Exploring the interplay of alcohol policies with drinking cultures and drinking practices. Paper presented at the Kettil Bruun Society Thematic Conference on Alcohol Policy Research, Melbourne, Australia Google Scholar

- de Looze, M., Raaijmakers, Q., ter Bogt, T., Bendtsen, P., Farhat, T., Ferreira, M. … Pickett, W. (2015). Decreases in adolescent weekly alcohol use in Europe and North America: Evidence from 28 countries from 2002 to 2010. European Journal of Public Health , 25(Suppl. 2), 69–72. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckv031 PubMed Web of Science ® Google Scholar

- Douglas, M. (1987). A distinctive anthropological perspective. In Douglas, M. (Ed.), Constructive drinking: Perspectives on drink from anthropology (pp. 3–15). New York/Cambridge: Cambridge University Press Google Scholar

- Duff, C. (2008). The pleasure in context. International Journal of Drug Policy , 19 , 384–392. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2012.12.009 PubMed Web of Science ® Google Scholar

- Duff, C. (2013). The social life of drugs. International Journal of Drug Policy , 3 , 167–172. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2007.07.003 Web of Science ® Google Scholar

- Eckert, P. (1989). Jocks and burnouts: Social categories and identities in the high school . New York and London: Teachers College Press Google Scholar

- Fortin, M., Bélanger, R.E., & Moulin, S. (2015). Typology of Canadian alcohol users relationships between use, context, and motivation to drink in the definition of drinking profiles. Contemporary Drug Problems . . [Epub ahead of print]. doi: 10.1177/0091450915600119 Google Scholar

- Gefou-Madianou, D. (1992). Exclusion and unity, retsina and sweet wine: Comensality and gender in a Greek agrotown. In Gefou-Madianou, D. (Ed.), Alcohol, gender and culture (pp. 1–34). New York: Routledge Google Scholar

- Gmel, G., Room, R., Kuendig, H., & Kuntsche, S. (2007). Detrimental drinking patterns: Empirical validation of the pattern values score of the Global Burden of Disease 2000 study in 13 countries. Journal of Substance Use , 12 , 337–358. doi: 10.1080/14659890701249624 Google Scholar

- Gordon, R., Heim, D., & MacAskill, S. (2012). Rethinking drinking cultures: A review of drinking cultures and a reconstructed dimensional approach. Public Health , 126 , 3–11. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2011.09.014 PubMed Web of Science ® Google Scholar

- Grace, J., Moore, D., & Northcote, J. (2009). Alcohol, risk and harm reduction: Drinking amongst young adults in recreational settings in Perth . Perth: Curtin University of Technology Google Scholar

- Grant, M.J., & Booth, A. (2009). A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information & Libraries Journal , 26 , 91–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x PubMed Web of Science ® Google Scholar

- Greeley, A.M., & McCready, W.C. (1978). Part two: A preliminary reconnaissance into the persistence and explanation of ethnic subcultural drinking patterns. Medical Anthropology , 2 , 31–51. doi: 10.1080/01459740.1978.9986961 Google Scholar

- Gutmann, M.C. (1999). Ethnicity, alcohol and acculturation. Social Science and Medicine , 48 , 173–184. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(98)00325-6 PubMed Web of Science ® Google Scholar

- Hall, S., & Jefferson, T. (1976). Resistance through rituals: Youth subcultures in post-war Britain . New York: Holmes & Meier Publishers Google Scholar

- Hannerz, U. (1992). The global ecumene as a network of networks. In: Kuper, A. (Ed.), Conceptualizing society (pp. 34–56). London: Routledge Google Scholar

- Härkönen, J.T., Törrönen, J., Mustonen, H., & Mäkelä, P. (2013). Changes in Finnish drinking occasions between 1976 and 2008 – The waxing and waning of drinking contexts. Addiction Research and Theory , 21 , 318–328. doi: 10.3109/16066359.2012.727506 Web of Science ® Google Scholar

- Hart, A. (2015). Assembling interrelations between low socioeconomic status and acute alcohol-related harms among young adult drinkers. Contemporary Drug Problems , 42 , 148–167. doi: 10.1177/0091450915583828 Google Scholar

- Heath, D.B. (1987). A decade of development in the anthropological study of alcohol use: 1970–1980. In Douglas, M. (Ed.), Constructive drinking: Perspectives on drinking from anthropology (pp. 16–69). New York/Cambridge: Cambridge University Press Google Scholar

- Hellman, M., & Rolando, S. (2013). Collectivist and individualist values traits in Finnish and Italian adolescents' alcohol norms. Drugs and Alcohol Today , 13 , 51–59. doi: 10.1108/17459261311310853 Google Scholar

- Her Majesty’s Government. (2012). The Government’s alcohol strategy . London: Her Majesty’s Government Google Scholar

- Hunt, G., & Barker, J.C. (2001). Socio-cultural anthropology and alcohol and drug research: Towards a unified theory. Social Science & Medicine , 53 , 165–188. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00329-4 PubMed Web of Science ® Google Scholar

- Hutton, F., Wright, S., & Saunders, E. (2013). Cultures of intoxication: Young women, alcohol, and harm reduction. Contemporary Drug Problems , 40 , 451–480. doi: 10.1177/009145091304000402 Google Scholar

- Keane, H. (2009). Intoxication, harm and pleasure: An analysis of the Australian National Alcohol Strategy. Critical Public Health , 19 , 135–142. doi: 10.1080/09581590802350957 Google Scholar

- Jayne, M., Holloway, S.L., & Valentine, G. (2006). Drunk and disorderly: Alcohol, urban life and public space. Progress in Human Geography , 30 , 451–468. doi: 10.1191/0309132506ph618oa Web of Science ® Google Scholar

- Jepperson, R., & Swidler, A. (1994). What properties of culture should we measure? Poetics , 22 , 359–371. doi: 10.1016/0304-422X(94)90014-0 Web of Science ® Google Scholar

- Kroeber, A.L., & Kluckhohn, C. (1952). Culture: A critical review of concepts and definitions . New York: Vintage Books Google Scholar

- Leifman, H. (2001). Homogenisation in alcohol consumption in the European Union. Nordic Studies on Alcohol and Drugs , 18, 15–30 Google Scholar

- Lemert, E.M. (1965). Comment on Mandelbaum’s article ‘Alcohol and culture’. Current Anthropology , 6, 291 Google Scholar

- Lemert, E.M. (1962). Alcohol, values and social control. In Pittman, D.J., & Snyder, C.R. (Eds.), Society, culture and drinking patterns (pp. 553–571). New York & London: Wiley Google Scholar

- Loughran, H. (2010). Eighteen and celebrating: Birthday cards and drinking culture. Journal of Youth Studies , 13 , 631–645. doi:10.1080/13676261003801721 Web of Science ® Google Scholar

- MacAndrew, C., & Edgerton, R.B. (1969). Drunken comportment: A social explanation . Chicago: Aldine Google Scholar

- Mäkelä, K. (1983). The uses of alcohol and their cultural regulation. Acta Sociologica , 26 , 21–31. doi: 10.1177/000169938302600102 Web of Science ® Google Scholar

- Mäkelä, P., Tigerstedt, C., & Mustonen, H. (2012). The Finnish drinking culture: Change and continuity in the past 40 years. Drug and Alcohol Review , 31 , 831–840. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2012.00479.x PubMed Web of Science ® Google Scholar

- Mandelbaum, D.G. (1965). Reply [to comments on his ‘Alcohol and culture’]. Current Anthropology , 6, 292–293 Google Scholar

- McCulloch, K., Stewart, A., & Lovegreen, N. (2006). ‘We just hang out together’: Youth cultures and social class. Journal of Youth Studies , 9 , 539–556. doi: 10.1080/13676260601020999 Google Scholar

- Measham, F., & Brain, K. (2005). ‘Binge’drinking, British alcohol policy and the new culture of intoxication. Crime, Media, Culture , 1 , 262–283. doi: 10.1177/1741659005057641 Google Scholar

- Mills, B.A., & Caetano, R. (2012). Decomposing associations between acculturation and drinking in Mexican Americans. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research , 36 , 1205–1211. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01712.x PubMed Web of Science ® Google Scholar

- Ministerial Council on Drug Strategy. (2006). National Alcohol Strategy 2006–2009 . Canberra: Ministerial Council on Drug Strategy Google Scholar

- Mizruchi, E.H., & Perrucci, R. (1970). Prescription, proscription and permissiveness: Aspects of norms and deviant drinking behavior . New Haven: College and University Press Google Scholar

- Moore, D. (2004). Beyond subculture in the ethnography of illicit drug use. Contemporary Drug Problems , 31 , 181–212. doi: 10.1177/009145090403100202 Google Scholar

- Moore, K., & Measham, F. (2012). Impermissible pleasures in UK leisure: Exploring policy developments in alcohol and illicit drugs. In Jones, C., Barclay, E., & Mawby, R.I. (Eds.), The problem of pleasure: Leisure, tourism and crime (pp. 62–76). London: Routledge Google Scholar

- Mustonen, H., Mäkelä, P., & Lintonen, T. (2014). Toward a typology of drinking occasions: Latent classes of an autumn week's drinking occasions. Addiction Research and Theory , 22 , 524–534. doi: 10.3109/16066359.2014.911845 Web of Science ® Google Scholar

- O'Malley, P., & Valverde, M. (2004). Pleasure, freedom and drugs: The uses of ‘pleasure' in liberal governance of drug and alcohol consumption. Sociology , 38 , 25–42. doi: 10.1177/0038038504039359 Google Scholar

- Partanen, J. (1991). Sociability and intoxication: Alcohol and drinking in Kenya, Africa, and the modern world (Vol. 39). Helsinki: Finnish Foundation for Alcohol Studies Google Scholar

- Pennay, A. (2012). Carnal pleasures and grotesque bodies: Regulating the body during a “big night out” of alcohol and party drug use. Contemporary Drug Problems , 39 , 397–428. doi: 10.1177/009145091203900304 Google Scholar

- Pennay, A., Livingston, M., & MacLean, S. (2015). Young people are drinking less: It’s time to find out why. Drug and Alcohol Review , 34 , 115–118. doi: 10.1111/dar.12255 PubMed Web of Science ® Google Scholar

- Petrilli, E., Beccaria, F., Prina, F., & Rolando, S. (2014). Images of alcohol among Italian adolescents: Understanding their point of view. Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy , 21 , 211–220. doi: 10.3109/09687637.2013.875128 Web of Science ® Google Scholar

- Pittman, D.J. (1967). International overview: Social and cultural factors in drinking patterns, pathological and nonpathological. In Pittman, D.J. (Ed.), Alcoholism (pp. 3–20). New York: Harper & Row Google Scholar

- Raitasalo, K., Holmila, M., & Mäkelä, P. (2011). Drinking in the presence of underage children: Attitudes and behaviour. Addiction Research and Theory , 19 , 394–401. doi: 10.3109/16066359.2011.560693 Web of Science ® Google Scholar

- Ritter, A. (2014). Where is the pleasure? Addiction , 109, 1587–1588 PubMed Web of Science ® Google Scholar

- Roberts, M. (2015). ‘A big night out’: Young people’s drinking, social practice and spatial experience in the ‘liminoid’zones of English night-time cities. Urban Studies , 52 , 571–588. doi: 10.1177/0042098013504005 Web of Science ® Google Scholar

- Rolando, S., Beccaria, F., Tigerstedt, C., & Törrönen, J. (2012). First drink: What does it mean? the alcohol socialization process in different drinking cultures. Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy , 19 , 201–212. doi: 10.3109/09687637.2012.658105 Web of Science ® Google Scholar

- Rolando, S., & Katainen, A. (2014). Images of alcoholism among adolescents in individualistic and collectivistic geographies. NAD Nordic Studies on Alcohol and Drugs , 31 , 189–205. doi: 10.2478/nsad-2014-0015 Web of Science ® Google Scholar

- Room, R. (1975). Normative perspectives on alcohol use and problems. Journal of Drug Issues , 5 , 358–368. doi: 10.1177/002204267500500407 Web of Science ® Google Scholar

- Room, R. (1976). Ambivalence as a sociological explanation: The case of cultural explanations of alcohol problems. American Sociological Review , 41, 1047–1065 PubMed Web of Science ® Google Scholar

- Room, R. (1985). Foreword. In Bennett, L.A., & Ames, G.M. (Eds.), The American experience with alcohol: Contrasting cultural perspectives (pp. xi–xvii). New York and London: Plenum Google Scholar

- Room, R. (2005). Multicultural contexts and alcohol and drug use as symbolic behaviour. Addiction Research and Theory , 13 , 321–331. doi: 10.1080/16066350500136326 Web of Science ® Google Scholar

- Room, R. (2010). Dry and wet cultures in the age of globalization. Salute e Società , 10(Suppl. 3), 229–237 Google Scholar

- Room, R., & Mäkelä, K. (2000). Typologies of the cultural position of drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol , 61, 475–483. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.15288/jsa.2000.61.475 PubMed Web of Science ® Google Scholar

- Room, R., & Mitchell, A. (1972). Notes on cross-national and cross-cultural studies. Drinking and Drug Practices Surveyor , 5, 16–20 Google Scholar

- Sargent, M.J. (1968). Heavy drinking and its relation to alcoholism – with special reference to Australia. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Sociology , 4, 146–157. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/144078336800400206 Web of Science ® Google Scholar

- Shoveller, J., Viehbeck, S., Di Ruggiero, E., Greyson, D., Thomson, K., & Knight, R. (2015). A critical examination of representations of context within research on population health interventions. Critical Public Health . [Epub ahead of print]. DOI: 10.1080/09581596.2015.1117577 Google Scholar

- Stickley, A., Jukkala, T., & Norstrom, T. (2011). Alcohol and suicide in Russia, 1870-1894 and 1956-2005: Evidence for the continuation of a harmful drinking culture across time? Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs , 72, 341–347. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.15288/jsad.2011.72.341 PubMed Web of Science ® Google Scholar

- Stivers, R. (1976). A hair of the dog: Irish drinking and American stereotype . University Park, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press Google Scholar

- Straw, W. (1991). Systems of articulation, logics of change: Communities and scenes in popular music. Cultural Studies , 5 , 368–388. doi: 10.1080/09502389100490311 Google Scholar

- Sulkunen, P. (1976). Drinking patterns and the level of alcohol consumption: An international overview. In Gibbins, R., Israel, Y., Kalant, H., Popham, R.E., Schmidt, W., & Smart, R.G. (Eds.), Research advances in alcohol and drug problems (Vol. 3). New York: Wiley Google Scholar

- Sulkunen, P. (1983). Alcohol consumption and the transformation of living conditions. In Smart, R.G., Glaser, F.B., Israel, Y., Kalant, H., Popham, R.E., & Schmidt, W. (Ed.), Research advances in alcohol and drug problems (Vol. 7, pp. 247–298). New York: Plenum Press Google Scholar

- Taras, V., Rowney, J., & Steel, P. (2009). Half a century of measuring culture: Review of approaches, challenges, and limitations based on the analysis of 121 instruments for quantifying culture. Journal of International Management , 15 , 357–373. doi: 10.1016/j.intman.2008.08.005 Web of Science ® Google Scholar

- Thornton, S. (1995). Club cultures: Music, media and subcultural capital . Cambridge: Polity Press Google Scholar

- Ullman, A.D. (1958). Sociocultural backgrounds of alcoholism. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science , 315 , 48–54. doi: 10.1177/000271625831500107 Web of Science ® Google Scholar

- Unruh, D.R. (1980). The nature of social worlds. Pacific Sociological Review , 23 , 271–296. doi: 10.2307/1388823 Google Scholar

- Valentine, G., Holloway, S., Knell, C., & Jayne, M. (2008). Drinking places: Young people and cultures of alcohol consumption in rural environments. Journal of Rural Studies , 24, 28–40 Web of Science ® Google Scholar

- Victorian Government. (2008). Victoria’s Alcohol Action Plan 2008–2013: Restoring the balance . Melbourne: Victorian Government Google Scholar

- White, A., Castle, I.J.P., Chen, C.M., Shirley, M., Roach, D., & Hingson, R. (2015). Converging patterns of alcohol use and related outcomes among females and males in the United States, 2002 to 2012. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research , 39 , 1712–1726. doi: 10.1177/002204267500500407 PubMed Web of Science ® Google Scholar

- Winlow, S., & Hall, S. (2006). Violent night: Urban leisure and contemporary culture . Oxford: Berg Google Scholar

- Yinger, M. (1960). Contraculture and subculture. American Sociological Review , 25, 625–635 Web of Science ® Google Scholar

Reprints and Corporate Permissions

Please note: Selecting permissions does not provide access to the full text of the article, please see our help page How do I view content?

To request a reprint or corporate permissions for this article, please click on the relevant link below:

Academic Permissions

Obtain permissions instantly via Rightslink by clicking on the button below:

If you are unable to obtain permissions via Rightslink, please complete and submit this Permissions form . For more information, please visit our Permissions help page .

- Back to Top

Related research

People also read lists articles that other readers of this article have read.

Recommended articles lists articles that we recommend and is powered by our AI driven recommendation engine.

Cited by lists all citing articles based on Crossref citations. Articles with the Crossref icon will open in a new tab.

- People also read

- Recommended articles

To cite this article:

Download citation, your download is now in progress and you may close this window.

- Choose new content alerts to be informed about new research of interest to you

- Easy remote access to your institution's subscriptions on any device, from any location

- Save your searches and schedule alerts to send you new results

- Export your search results into a .csv file to support your research

Login or register to access this feature

Register now or learn more

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Sweepstakes

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

How Does Alcohol Affect Society?

- Financial Cost

- Aggression and Violence

- Impact on the Family

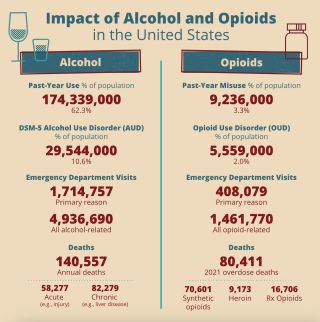

Alcohol is the most commonly used drug among U.S. adults. Alcohol use is associated with a wide range of health risks and other problems for individuals. But the costs of alcohol don't just affect the person drinking.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), excessive alcohol use costs the U.S. almost a quarter trillion dollars a year. Economic costs are one part of the toll, but there are also other societal issues that are tied to alcohol use.

At a Glance

The real-world impact of alcohol abuse reaches far beyond the financial costs. When a loved one has a problem with alcohol, it can affect their marriage and their extended family. There's also a larger impact on the community, schools, the workplace, the healthcare system, and society as a whole.

How Alcohol Affects Society

Alcohol use can affect society in terms of:

- Economic costs linked to increased healthcare expenses, lost productivity, and legal costs

- Health consequences caused by health problems caused by alcohol as well as accidents, injuries, and violence connected to alcohol use

- Legal consequences , including increased crime, drunk driving accidents, and other issues related to law enforcement and criminal justice

- Family effects , including child abuse, neglect, intimate partner violence, and substance use problems in children

- Educational costs associated with worse academic performance and achievement

Such costs are often linked to those who have alcohol use disorders. According to the 2021 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), 29.5 million people over the age of 12 (10.6% of the population) had an alcohol use disorder in the past year. Estimates suggest that approximately 13.9% of people in the United States will meet the criteria for severe alcohol use disorder in their lifetimes.

However, it's not necessarily people with alcohol addiction having the biggest impact on these figures. It's estimated that 77% of the cost of excessive alcohol consumption in the U.S. is due to binge drinking , and most binge drinkers are not alcohol dependent.

The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism states that 140,000 people die each year due to alcohol-related causes. Alcohol is the fourth leading preventable cause of death in the U.S.

Financial Costs of Alcoholism

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the cost of excessive alcohol use in the U.S. alone reaches $249 billion annually. Around 77% of that is attributed to binge drinking , defined as four or more alcoholic beverages per occasion for women or five or more drinks per occasion for men.

The CDC estimates that 40% of the cost of binge drinking is paid by federal, state, and local governments.

The CDC suggests that the most significant economic costs of alcohol use are due to the following:

- Lost workplace productivity (72% of the total cost)

- Healthcare expenses (11% of the total cost)

- Criminal justice expenses (10% of the total cost)

- Motor vehicle crash expenses (5% of the total cost)

The CDC estimates that these figures are all underestimated because alcohol's involvement in sickness, injury, and death is not always available or reported. These figures also do not include some medical and mental health conditions that are the result of alcohol abuse.

Also not included in these figures are the work days that family members miss due to the alcohol problems of a loved one.

Healthcare Expense of Alcohol Abuse

Alcohol consumption is a risk factor in numerous chronic diseases and conditions, and alcohol plays a significant role in certain cancers, psychiatric conditions, and numerous cardiovascular and digestive diseases. Additionally, alcohol consumption can increase the risk of diabetes, stroke, and heart disease.

An estimated $28 billion is spent each year on alcohol-related health care.

Alcohol-Related Aggression and Violence

Along with unintentional injury, alcohol plays a significant role in intentional injuries as a result of aggression and violence. Alcohol has been linked to physical violence by a variety of research studies.

On top of the healthcare cost of alcohol-related intentional violence in the United States, the estimated annual cost to the criminal justice system is another $25 billion.

Impact of Alcoholism on the Family

The social impact of alcohol abuse is a separate issue from the financial costs involved, and that impact begins in the home, extends into the community, and often affects society as a whole, much like the financial impact does.

Research on the effects of alcohol abuse on families shows that alcohol abuse and addiction play a role in intimate partner violence, cause families' financial problems, impair decision-making skills, and play a role in child neglect and abuse.

Long-term alcohol use leads to changes in the brain that affect decision-making, emotional processing, and self-control, making people who drink more susceptible to aggression and violence. According to the U.S. Department of Justice, alcohol makes intimate partner violence more frequent and severe.

As with the financial costs of alcohol abuse, studies have found occasional binge drinking can also affect families. Research suggests that the risk of intimate partner violence rises not only in the context of frequent drinking but also when a partner has consumed a large volume of drinks in one sitting.

If you or a loved one are struggling with substance use or addiction, contact the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) National Helpline at 1-800-662-4357 for information on support and treatment facilities in your area.

For more mental health resources, see our National Helpline Database .

Alcohol Abuse and Children

Fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASDs) are one of the most common direct consequences of parental alcohol use in the United States, caused by alcohol consumption by the mother during pregnancy. Children with FAS display various symptoms, many of which are lifelong and permanent.

Children who grow up in a home with a loved one dealing with alcohol addiction may be affected as well; they are at significant risk of developing alcohol use disorders themselves.

Growing up in a home where at least one parent has a severe alcohol use disorder can increase a child's chances of developing psychological and emotional problems.

The Bottom Line

Alcohol's effects go beyond it's effects on individual health and well-being; it also has steep economic and societal costs. The excess use of alcohol leads to billions in lost productivity and healthcare costs. It also has a heavy strain on families, communities, and society as a whole. Increased violence, injuries, accidents, child abuse, and intimate partner violence are all linked to alcohol use.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Excessive drinking is draining the U.S. economy .

National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Alcohol use disorder (AUD) in the United States: Age groups and demographic characteristics .

Grant BF, Goldstein RB, Saha TD, et al. Epidemiology of DSM-5 Alcohol Use Disorder: Results From the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions III . JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(8):757-766. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.0584

Esser MB, Hedden SL, Kanny D, Brewer RD, Gfroerer JC, Naimi TS. Prevalence of Alcohol Dependence Among US Adult Drinkers, 2009-2011 . Prev Chronic Dis. 2014;11:E206. doi:10.5888/pcd11.140329

National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Alcohol-related emergencies and deaths in the United States .

Rehm J. The Risks Associated With Alcohol Use and Alcoholism . Alcohol Res Health . 2011;34(2):135-143.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The cost of excessive alcohol use .

Wilson IM, Graham K, Taft A. Alcohol interventions, alcohol policy and intimate partner violence: a systematic review . BMC Public Health. 2014;14:881. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-14-881

Lander L, Howsare J, Byrne M. The impact of substance use disorders on families and children: From theory to practice . Soc Work Public Health . 2013;28(3-4):194-205. doi:10.1080/19371918.2013.759005

Sontate KV, Rahim Kamaluddin M, Naina Mohamed I, et al. Alcohol, aggression, and violence: From public health to neuroscience . Front Psychol . 2021;12:699726. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.699726

U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs. Who facts on: Intimate partner violence and alcohol .

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Basics about FASDS .

Moss HB. The impact of alcohol on society: A brief overview . Soc Work Public Health. 2013;28(3-4):175-177. doi:10.1080/19371918.2013.758987

Sacks JJ, Gonzales KR, Bouchery EE, Tomedi LE, Brewer RD. 2010 National and State Costs of Excessive Alcohol Consumption . Am J Prev Med . 2015;49(5):e73-e79. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2015.05.031

By Buddy T Buddy T is a writer and founding member of the Online Al-Anon Outreach Committee with decades of experience writing about alcoholism. Because he is a member of a support group that stresses the importance of anonymity at the public level, he does not use his photograph or his real name on this website.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

Social and Cultural Contexts of Alcohol Use: Influences in a Social-Ecological Framework

Affiliations.

- 1 Department of Epidemiology and Biostatics and Global Health Group at the University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, California.

- 2 School of Social Work, Boston College, Boston, Massachusetts.

- PMID: 27159810

- PMCID: PMC4872611