Piaget’s Theory and Stages of Cognitive Development

Saul McLeod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul McLeod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

Key Features

- Developmental Stages : Piaget proposed four sequential stages of cognitive development, each marked by distinct thinking patterns, progressing from infancy to adolescence.

- Constructivist Approach to Learning : Children actively build understanding by exploring their environment as “little scientists,” rather than passively absorbing information.

- Schemas : Mental frameworks for organizing information, growing in number and complexity as children develop, enabling deeper world understanding.

- Assimilation : Integration of new information into existing schemas.

- Accommodation : Modifying existing schemas or creating new ones to fit new information.

- Equilibration : Process of balancing assimilation and accommodation to progress through cognitive stages, resolving conflicts and shifting to new thought patterns.

Stages of Development

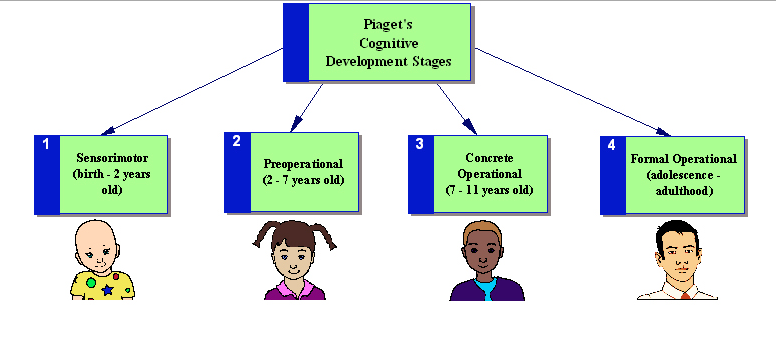

Jean Piaget’s theory of cognitive development suggests that children move through four different stages of intellectual development which reflect the increasing sophistication of children’s thought.

Each child goes through the stages in the same order (but not all at the same rate), and child development is determined by biological maturation and interaction with the environment.

At each stage of development, the child’s thinking is qualitatively different from the other stages, that is, each stage involves a different type of intelligence.

Although no stage can be missed out, there are individual differences in the rate at which children progress through stages, and some individuals may never attain the later stages.

Piaget did not claim that a particular stage was reached at a certain age – although descriptions of the stages often include an indication of the age at which the average child would reach each stage.

The Sensorimotor Stage

Ages: birth to 2 years.

During the sensorimotor stage (birth to age 2) infants develop basic motor skills and learn to perceive and interact with their environment through physical sensations and body coordination.

Major Characteristics and Developmental Changes:

- The infant learns about the world through their senses and through their actions (moving around and exploring their environment).

- During the sensorimotor stage, a range of cognitive abilities develop. These include: object permanence; self-recognition (the child realizes that other people are separate from them); deferred imitation; and representational play.

- Cognitive abilities relate to the emergence of the general symbolic function, which is the capacity to represent the world mentally.

- At about 8 months, the infant will understand the permanence of objects and that they will still exist even if they can’t see them, and the infant will search for them when they disappear.

At the beginning of this stage, the infant lives in the present. It does not yet have a mental picture of the world stored in its memory, so it does not have a sense of object permanence.

If the child cannot see something, then it does not exist. This is why you can hide a toy from an infant, while it watches, but it will not search for the object once it has gone out of sight.

The main achievement during this stage is object permanence – knowing that an object still exists, even if it is hidden. It requires the ability to form a mental representation (i.e., a schema) of the object.

Towards the end of this stage the general symbolic function begins to appear where children show in their play that they can use one object to stand for another. Language starts to appear because they realise that words can be used to represent objects and feelings.

The child begins to be able to store information about the world, recall it, and label it.

Individual Differences

- Cultural Practices : In some cultures, babies are carried on their mothers’ backs throughout the day. This constant physical contact and varied stimuli can influence how a child perceives their environment and their sense of object permanence.

- Gender Norms : Toys assigned to babies can differ based on gender expectations. A boy might be given more cars or action figures, while a girl might receive dolls or kitchen sets. This can influence early interactions and sensory explorations.

Learn More: The Sensorimotor Stage of Cognitive Development

The Preoperational Stage

Ages: 2 – 7 years.

Piaget’s second stage of intellectual development is the preoperational stage , which occurs between 2 and 7 years. At the beginning of this stage, the child does not use operations (a set of logical rules), so thinking is influenced by how things look or appear to them rather than logical reasoning.

For example, a child might think a tall, thin glass contains more liquid than a short, wide glass, even if both hold the same amount, because the child focuses on the height rather than considering both dimensions.

Furthermore, the child is egocentric; he assumes that other people see the world as he does, as shown in the Three Mountains study.

As the preoperational stage develops, egocentrism declines, and children begin to enjoy the participation of another child in their games, and let’s pretend play becomes more important.

Toddlers often pretend to be people they are not (e.g. superheroes, policemen), and may play these roles with props that symbolize real-life objects. Children may also invent an imaginary playmate.

- Toddlers and young children acquire the ability to internally represent the world through language and mental imagery.

- During this stage, young children can think about things symbolically. This is the ability to make one thing, such as a word or an object, stand for something other than itself.

- A child’s thinking is dominated by how the world looks, not how the world is. It is not yet capable of logical (problem-solving) type of thought.

- Moreover, the child has difficulties with class inclusion; he can classify objects but cannot include objects in sub-sets, which involves classifying objects as belonging to two or more categories simultaneously.

- Infants at this stage also demonstrate animism. This is the tendency for the child to think that non-living objects (such as toys) have life and feelings like a person’s.

By 2 years, children have made some progress toward detaching their thoughts from the physical world. However, have not yet developed logical (or “operational”) thought characteristics of later stages.

Thinking is still intuitive (based on subjective judgments about situations) and egocentric (centered on the child’s own view of the world).

- Cultural Storytelling : Different cultures have unique stories, myths, and folklore. Children from diverse backgrounds might understand and interpret symbolic elements differently based on their cultural narratives.

- Race & Representation : A child’s racial identity can influence how they engage in pretend play. For instance, a lack of diverse representation in media and toys might lead children of color to recreate scenarios that don’t reflect their experiences or background.

Learn More: The Preoperational Stage of Cognitive Development

The Concrete Operational Stage

Ages: 7 – 11 years.

By the beginning of the concrete operational stage , the child can use operations (a set of logical rules) so they can conserve quantities, realize that people see the world in a different way (decentring), and demonstrate improvement in inclusion tasks.

Children still have difficulties with abstract thinking.

- During this stage, children begin to think logically about concrete events.

- Children begin to understand the concept of conservation; understanding that, although things may change in appearance, certain properties remain the same.

- During this stage, children can mentally reverse things (e.g., picture a ball of plasticine returning to its original shape).

- During this stage, children also become less egocentric and begin to think about how other people might think and feel.

The stage is called concrete because children can think logically much more successfully if they can manipulate real (concrete) materials or pictures of them.

Piaget considered the concrete stage a major turning point in the child’s cognitive development because it marks the beginning of logical or operational thought. This means the child can work things out internally in their head (rather than physically try things out in the real world).

Children can conserve number (age 6), mass (age 7), and weight (age 9). Conservation is the understanding that something stays the same in quantity even though its appearance changes.

But operational thought is only effective here if the child is asked to reason about materials that are physically present. Children at this stage will tend to make mistakes or be overwhelmed when asked to reason about abstract or hypothetical problems.

- Cultural Context in Conservation Tasks : In a society where resources are scarce, children might demonstrate conservation skills earlier due to the cultural emphasis on preserving and reusing materials.

- Gender & Learning : Stereotypes about gender abilities, like “boys are better at math,” can influence how children approach logical problems or classify objects based on perceived gender norms.

Learn More: The Concrete Operational Stage of Development

The Formal Operational Stage

Ages: 12 and over.

The formal operational period begins at about age 11. As adolescents enter this stage, they gain the ability to think abstractly, the ability to combine and classify items in a more sophisticated way, and the capacity for higher-order reasoning.

Adolescents can think systematically and reason about what might be as well as what is (not everyone achieves this stage). This allows them to understand politics, ethics, and science fiction, as well as to engage in scientific reasoning.

Adolescents can deal with abstract ideas; for example, they can understand division and fractions without having to actually divide things up, and solve hypothetical (imaginary) problems.

- Concrete operations are carried out on physical objects, whereas formal operations are carried out on ideas. Formal operational thought is entirely freed from physical and perceptual constraints.

- During this stage, adolescents can deal with abstract ideas (e.g., they no longer need to think about slicing up cakes or sharing sweets to understand division and fractions).

- They can follow the form of an argument without having to think in terms of specific examples.

- Adolescents can deal with hypothetical problems with many possible solutions. For example, if asked, ‘What would happen if money were abolished in one hour?’ they could speculate about many possible consequences.

- Piaget described reflective abstraction as the process by which individuals become aware of and reflect upon their own cognitive actions or operations (metacognition).

From about 12 years, children can follow the form of a logical argument without reference to its content. During this time, people develop the ability to think about abstract concepts, and logically test hypotheses.

This stage sees the emergence of scientific thinking , formulating abstract theories and hypotheses when faced with a problem.

- Culture & Abstract Thinking : Cultures emphasize different kinds of logical or abstract thinking. For example, in societies with a strong oral tradition, the ability to hold complex narratives might develop prominently.

- Gender & Ethics : Discussions about morality and ethics can be influenced by gender norms . For instance, in some cultures, girls might be encouraged to prioritize community harmony, while boys might be encouraged to prioritize individual rights.

Learn More: The Formal Operational Stage of Development

Piaget’s Theory

- Piaget’s theory places a strong emphasis on the active role that children play in their own cognitive development.

- According to Piaget, children are not passive recipients of information; instead, they actively explore and interact with their surroundings.

- This active engagement with the environment is crucial because it allows them to gradually build their understanding of the world.

1. History of Piaget’s Theory of Cognitive Development

Piaget was employed at the Binet Institute in the 1920s, where his job was to develop French versions of questions on English intelligence tests. He became intrigued with the reasons children gave for their wrong answers to the questions that required logical thinking.

He believed that these incorrect answers revealed important differences between the thinking of adults and children.

Piaget branched out on his own with a new set of assumptions about children’s intelligence:

- Children’s intelligence differs from an adult’s in quality rather than in quantity. This means that children reason (think) differently from adults and see the world in different ways.

- Children actively build up their knowledge about the world . They are not passive creatures waiting for someone to fill their heads with knowledge.

- The best way to understand children’s reasoning is to see things from their point of view.

Piaget did not want to measure how well children could count, spell, or solve problems as a way of grading their I.Q.

He was more interested in how fundamental concepts emerged, such as the very ideas of number, time, quantity, causality, and justice .

Piaget studied children from infancy to adolescence using naturalistic observation of his own three babies and sometimes controlled observation too. From these, he wrote diary descriptions charting their development.

He also used clinical interviews and observations of older children who were able to understand questions and hold conversations.

2. Piaget’s Clinical Method

Piaget’s clinical method is a research technique used to investigate children’s cognitive development.

It is a research approach for understanding children’s thinking that Piaget adapted from the diagnostic clinical interview used in psychopathology.

Unlike standardized tests, the clinical method uses flexible, open-ended questions to explore the child’s thinking in depth .

The interviewer adapts their questions based on the child’s initial responses, prompting further explanation and clarification.

Key characteristics of the clinical method:

- Piaget’s method emphasizes the importance of understanding the child’s perspective, rather than imposing adult ways of thinking on them.

- One key aspect of this approach is the use of open-ended and non-judgmental questions that allow the child to express their thoughts freely. The questions should be based on the spontaneous questions asked by children of the same age or younger.

- The interviewer must carefully observe the child’s responses and follow up with additional questions to clarify their reasoning.

- The interviewer must also be able to distinguish between truly spontaneous responses and those that are influenced by suggestion or other external factors.

Piaget provided detailed criteria for evaluating the quality of children’s responses, emphasizing the need to consider factors like resistance to suggestion, the depth of the child’s thinking, and the consistency of the response over time

Piaget’s clinical method has been influential in the field of developmental psycholog y and has helped to shape the way researchers and educators understand children’s thinking.

What is the “critical method” and how does it differ from the clinical method?

It’s important to note that the clinical method evolved throughout Piaget’s career.

As he continued to refine his approach, he began incorporating physical objects and manipulations into his interviews, leading to what he termed the critical method.

While the clinical method primarily relies on verbal dialogue, the critical method involves children actively manipulating objects, allowing researchers to observe their actions and reasoning in relation to physical phenomena.

For example, a researcher might ask a child to predict whether a ball of clay will weigh more or less after being rolled into a snake (conservation of mass).

By observing the child’s actions and explanations, researchers can gain insight into their understanding of the concept.

Piaget believed that engaging children with a concrete challenge helped to put them at ease, minimized the amount of verbal instruction required, and allowed the interviewer to use the child’s language when discussing the phenomenon.

By incorporating physical objects into his research, he could observe how children’s actions and manipulations influenced their thinking.

For example, to understand how children transition from animistic to mechanistic thinking, Piaget explored children’s conceptions of material force through a series of experiments involving physical demonstrations

However, the core principles of the clinical examination, such as open-ended inquiry, a focus on underlying reasoning, and sensitive interviewing, remained essential elements of his research, even as his methods became more complex

3. Piaget’s Theory Differs From Others In Several Ways:

Piaget’s (1936, 1950) theory of cognitive development explains how a child constructs a mental model of the world.

He disagreed with the idea that intelligence was a fixed trait, and regarded cognitive development as a process that occurs due to biological maturation and interaction with the environment.

Children’s ability to understand, think about, and solve problems in the world develops in a stop-start, discontinuous manner (rather than gradual changes over time).

Piaget’s theory:

- Is concerned with children, rather than learners of all ages.

- Focuses on development, rather than learning per se, so it does not address the learning of information or specific behaviors.

- Proposes discrete stages of development, marked by qualitative differences, rather than a gradual increase in the number and complexity of behaviors, concepts, ideas, etc.

The goal of the theory is to explain the mechanisms and processes by which the infant, and then the child, develops into an individual who can reason and think using hypotheses.

To Piaget, cognitive development was a progressive reorganization of mental processes as a result of biological maturation and environmental experience.

Children construct an understanding of the world around them, then experience discrepancies between what they already know and what they discover in their environment.

A schema is a mental framework or concept that helps us organize and interpret information. It’s like a mental file folder where we store knowledge about a particular object, event, or concept.

According to Piaget (1952), schemas are fundamental building blocks of cognitive development. They are constantly being created, modified, and reorganized as we interact with the world.

Wadsworth (2004) suggests that schemata (the plural of schema) be thought of as “index cards” filed in the brain, each one telling an individual how to react to incoming stimuli or information.

According to Piaget, we are born with a few primitive schemas, such as sucking, which give us the means to interact with the world. These initial schemas are physical, but as the child develops, they become mental schemas.

Examples of Innate Schemas:

- Babies have a sucking reflex, triggered by something touching their lips. This corresponds to a “sucking schema.”

- The grasping reflex, elicited when something touches the palm of a baby’s hand, represents another innate schema.

- The rooting reflex, where a baby turns its head towards something that touches its cheek, is also considered an innate schema.

When Piaget discussed the development of a person’s mental processes, he referred to increases in the number and complexity of the schemata that the person had learned.

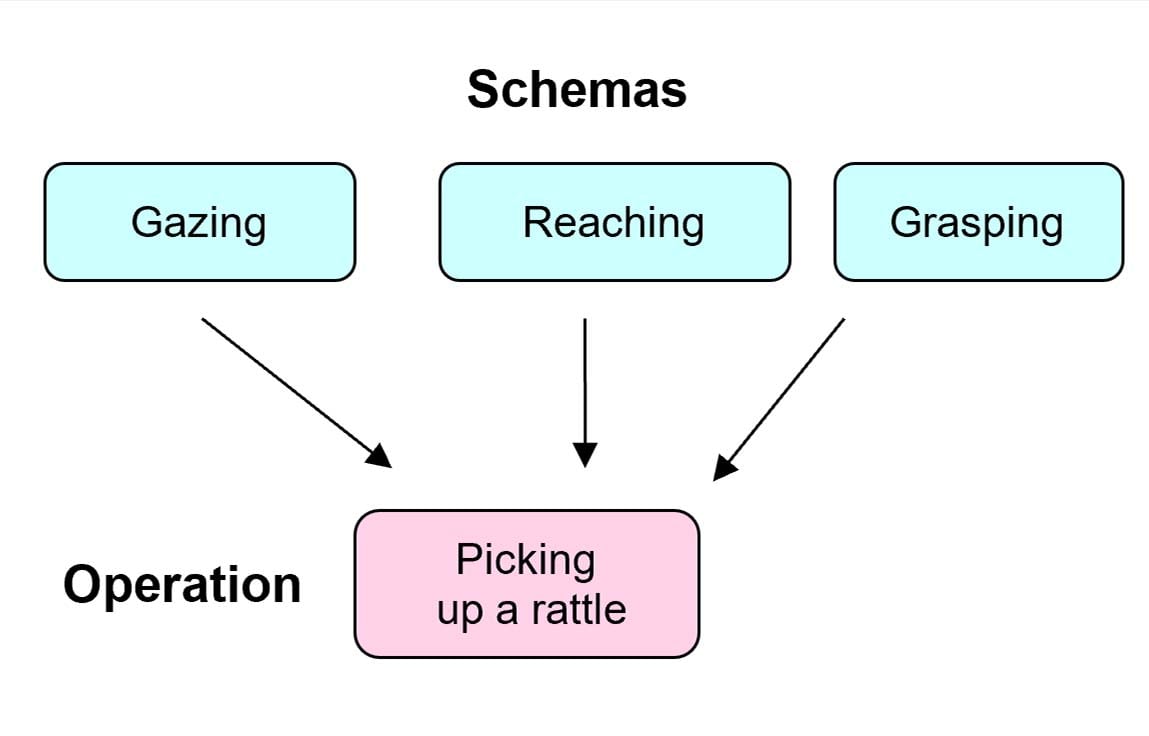

Operations are more sophisticated mental structures that allow us to combine schemas in a logical (reasonable) way. For example, picking up a rattle would combine three schemas, gazing, reaching and grasping.

As children grow, they can carry out more complex operations and begin to imagine hypothetical (imaginary) situations.

Operations are learned through interaction with other people and the environment, and they represent a key advancement in cognitive development beyond simple schemas.

As children grow and interact with their environment, these basic schemas become more complex and numerous, and new schemas are developed through the processes of assimilation and accommodation .

5. The Process of Adaptation

Jean Piaget (1952) viewed intellectual growth as a process of adaptation (adjustment) to the world.

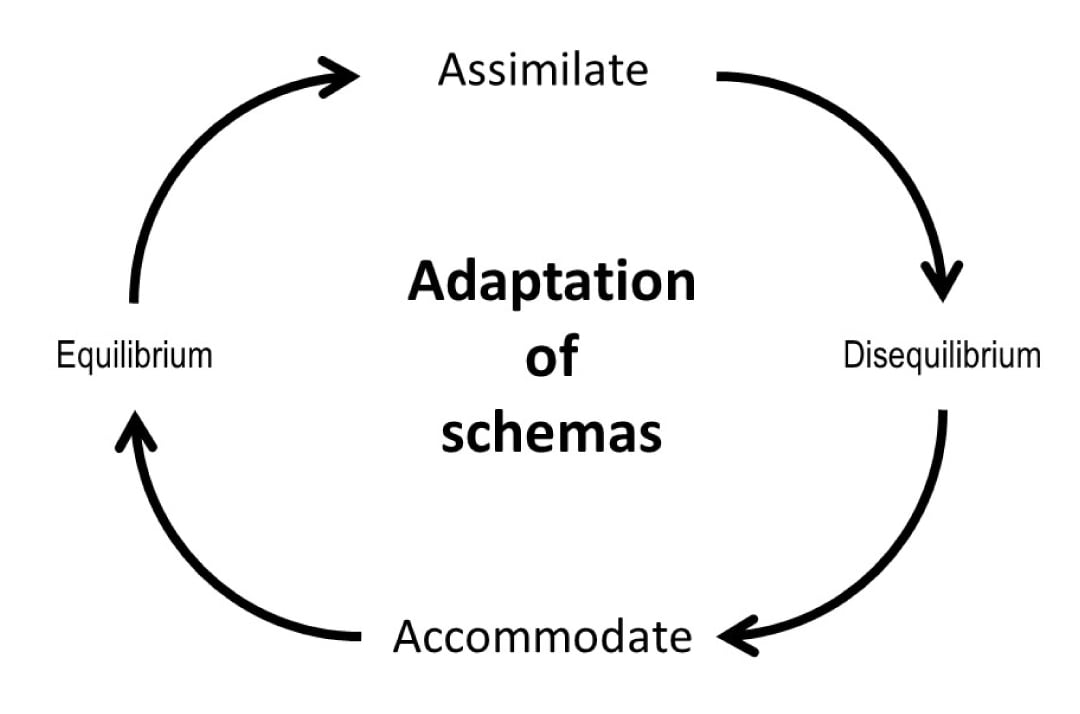

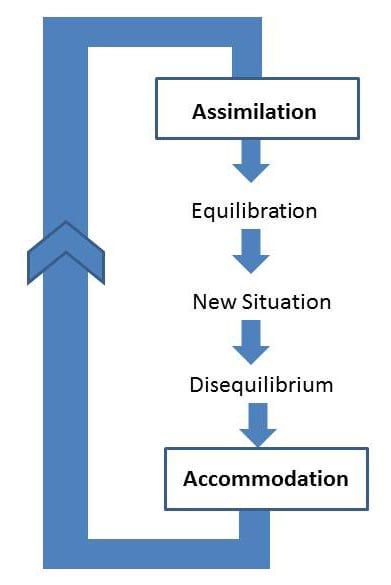

This happens through assimilation, accommodation, equilibration, and disequilibrium.

- Assimilation is fitting new information into existing schemas without changing one’s understanding. For example, a child who has only seen small dogs might call a cat a “dog” due to similar features like fur, four legs, and a tail.

- Accommodation occurs when existing schemas must be revised to incorporate new information. For instance, a child who believes all animals have four legs would need to accommodate their schema upon seeing a snake.

- A baby tries to use the same grasping schema to pick up a very small object. It doesn’t work. The baby then changes ( accommodates ) the schema using the forefinger and thumb to pick up the object.

When a child’s existing schemas are capable of explaining what it can perceive around it, it is said to be in a state of equilibrium , i.e., a state of cognitive (i.e., mental) balance.

Disequilibrium occurs when new information conflicts with existing schemas, creating cognitive discomfort. This cognitive conflict drives cognitive development and learning.

When encountering new information, a child first attempts to assimilate it into existing schemas.

If assimilation fails, disequilibrium occurs, prompting the need for accommodation.

Through accommodation , the child adjusts their schemas to restore equilibrium .

This cycle continues, driving cognitive development in a non-linear fashion – progressing through “leaps and bounds” rather than at a steady rate.

Importance of Equilibration:

Equilibration acts as a regulatory mechanism, balancing assimilation and accommodation. This balance is crucial because:

- Constant assimilation without accommodation would prevent the learning of new concepts.

- Constant accommodation without assimilation would make every experience seem novel, leading to cognitive exhaustion.

By maintaining this balance, equilibration facilitates cognitive growth, allowing children to build increasingly complex and accurate mental representations of the world.

Applications to Education

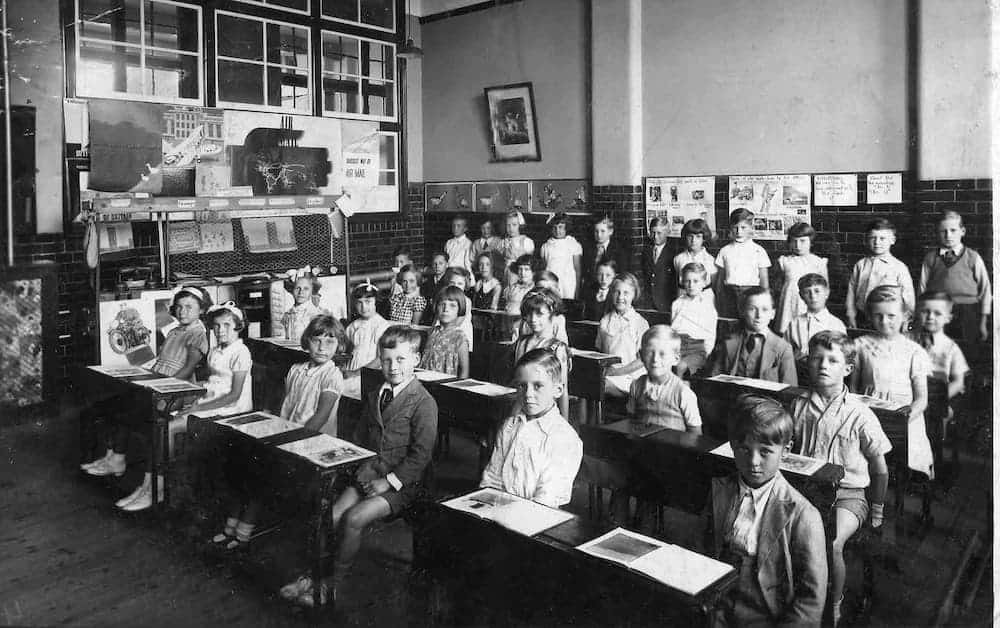

Think of old black-and-white films you’ve seen where children sat in rows at desks with inkwells. They learned by rote, all chanting in unison in response to questions set by an authoritarian figure like Miss Trunchbull in Matilda.

Children who were unable to keep up were seen as slacking and would be punished by variations on the theme of corporal punishment. Yes, it really did happen and in some parts of the world still does today.

Piaget is partly responsible for the change that occurred during the 1960s to early children’s education.

“Children should be able to do their own experimenting and their own research. Teachers, of course, can guide them by providing appropriate materials, but the essential thing is that in order for a child to understand something, he must construct it himself, he must re-invent it. Every time we teach a child something, we keep him from inventing it himself. On the other hand that which we allow him to discover by himself will remain with him visibly”. Piaget (1972, p. 27)

Plowden Report

In the 1960s, the Plowden Committee investigated deficiencies in United Kingdom education and incorporated many of Piaget’s ideas into its final report, published in 1967.

This was notable because Piaget’s (1952) work was not originally designed for educational applications.

The report made three key recommendations based on Piaget’s theories:

- Age-appropriate learning : The report recommended that educational activities and content should be tailored to match children’s cognitive developmental stages as outlined by Piaget. This meant ensuring that learning tasks were appropriate for the child’s current level of thinking and understanding.

- Concrete experiences : Following Piaget’s emphasis on the importance of concrete experiences in learning, especially for younger children, the report advocated for hands-on, experiential learning opportunities. This included recommendations for more practical activities and the use of manipulatives in the classroom.

- Active learning : The report emphasized the importance of children being active participants in their own learning, rather than passive recipients of information. This aligns with Piaget’s view that children construct their own understanding through interaction with their environment

The Plowden Report emphasized several recurring themes aligned with Piaget’s work:

- Individual learning

- Curriculum flexibility

- The central role of play in children’s learning

- Utilizing the environment for learning

- Discovery-based learning

- Assessment of children’s progress

Importantly, the report cautioned that teachers should “not assume that only what is measurable is valuable,” encouraging a holistic approach to assessing children’s development.

Educational Strategies Based on Piaget’s Theory

Teachers should encourage students to take an active role in discovering and constructing knowledge. The teacher’s role is to facilitate learning rather than direct tuition.

Because Piaget’s theory is based upon biological maturation and stages, the notion of “readiness” is important. Readiness concerns when certain information or concepts should be taught.

According to Piaget’s theory, children should not be taught certain concepts until they have reached the appropriate stage of cognitive development.

Consequently, education should be stage-specific, with curricula developed to match the age and stage of thinking of the child. For example, abstract concepts like algebra or atomic structure are not suitable for primary school children.

Assimilation and accommodation require an active learner, not a passive one, because problem-solving skills cannot be taught, they must be discovered (Piaget, 1958).

Therefore, teachers should encourage the following within the classroom:

- Consider the stages of cognitive development : Educational programs should be designed to correspond to Piaget’s stages of development. For example, a child in the concrete operational stage should not be taught abstract concepts and should be given concrete aid such as tokens to count with.

- Provide concrete experiences before abstract concepts : Especially for younger children, ensure they have hands-on experiences with concepts before introducing more abstract representations.

- Provide challenges that promote growth without causing frustration : Devising situations that present useful problems and create disequilibrium in the child.

- Focus on the process of learning rather than the end product : Instead of checking if children have the right answer, the teacher should focus on the students’ understanding and the processes they used to arrive at the answer.

- Encourage active learning : Learning must be active (discovery learning). Children should be encouraged to discover for themselves and to interact with the material instead of being given ready-made knowledge. Using active methods that require rediscovering or reconstructing “truths.”

- Foster social interaction: Using collaborative, as well as individual activities (so children can learn from each other). Implement cooperative learning activities, such as group problem-solving tasks or role-playing scenarios.

- Differentiated teaching : Adapt lessons to suit the needs of the individual child. For example, observe a child’s ability to classify objects by color, shape, and size. If they can easily sort by one attribute but struggle with multiple attributes, tailor future activities to gradually increase complexity, such as sorting buttons first by color, then by color and size together.

- Providing support for the “spontaneous research” of the child : Provide opportunities and resources for children to explore topics of their own interest, encouraging their natural curiosity and self-directed learning. Create a “Wonder Wall” in the classroom where children can post questions about topics that interest them.

Classroom Activities

Sensorimotor stage (0-2 years):.

Although most kids in this age range are not in a traditional classroom setting, they can still benefit from games that stimulate their senses and motor skills.

- Object Permanence Games : Play peek-a-boo or hide toys under a blanket to help babies understand that objects still exist even when they can’t see them.

- Sensory Play : Activities like water play, sand play, or playdough encourage exploration through touch.

- Imitation : Children at this age love to imitate adults. Use imitation as a way to teach new skills.

Preoperational Stage (2-7 years):

- Role Playing : Set up pretend play areas where children can act out different scenarios, such as a kitchen, hospital, or market.

- Use of Symbols : Encourage drawing, building, and using props to represent other things.

- Hands-on Activities : Children should interact physically with their environment, so provide plenty of opportunities for hands-on learning.

- Egocentrism Activities : Use exercises that highlight different perspectives. For instance, having two children sit across from each other with an object in between and asking them what the other sees.

Concrete Operational Stage (7-11 years):

- Classification Tasks : Provide objects or pictures to group, based on various characteristics.

- Hands-on Experiments : Introduce basic science experiments where they can observe cause and effect, like a simple volcano with baking soda and vinegar.

- Logical Games : Board games, puzzles, and logic problems help develop their thinking skills.

- Conservation Tasks : Use experiments to showcase that quantity doesn’t change with alterations in shape, such as the classic liquid conservation task using differently shaped glasses.

Formal Operational Stage (11 years and older):

- Hypothesis Testing : Encourage students to make predictions and test them out.

- Abstract Thinking : Introduce topics that require abstract reasoning, such as algebra or ethical dilemmas.

- Problem Solving : Provide complex problems and have students work on solutions, integrating various subjects and concepts.

- Debate and Discussion : Encourage group discussions and debates on abstract topics, highlighting the importance of logic and evidence.

- Feedback and Questioning : Use open-ended questions to challenge students and promote higher-order thinking. For instance, rather than asking, “Is this the right answer?”, ask, “How did you arrive at this conclusion?”

Individual Differences In Learning

While Piaget’s stages offer a foundational framework, they are not universally experienced in the same way by all children.

Social identities play a critical role in shaping cognitive development, necessitating a more nuanced and culturally responsive approach to understanding child development.

Piaget’s stages may manifest differently based on social identities like race, gender, and culture:

- Race & Teacher Interactions : A child’s race can influence teacher expectations and interactions. For example, racial biases can lead to children of color being perceived as less capable or more disruptive, influencing their cognitive challenges and support.

- Racial and Cultural Stereotypes : These can affect a child’s self-perception and self-efficacy . For instance, stereotypes about which racial or cultural groups are “better” at certain subjects can influence a child’s self-confidence and, subsequently, their engagement in that subject.

- Gender & Peer Interactions : Children learn gender roles from their peers. Boys might be mocked for playing “girl games,” and girls might be excluded from certain activities, influencing their cognitive engagements.

- Language : Multilingual children might navigate the stages differently, especially if their home language differs from their school language. The way concepts are framed in different languages can influence cognitive processing. Cultural idioms and metaphors can shape a child’s understanding of concepts and their ability to use symbolic representation, especially in the pre-operational stage.

Overcoming Challenges and Barriers in Implementing Piagetian Strategies

Balancing play and curriculum.

- Purposeful Play: Ensuring that play is not just free time but a structured learning experience requires careful planning. Educators must identify clear learning objectives and create play environments that facilitate these goals.

- Alignment with Standards: Striking a balance between child-initiated play and curriculum expectations can be challenging. Educators need to find ways to integrate play-based learning with broader educational goals and standards.

- Pace of Learning: The curriculum’s focus on specific content by certain ages can create pressure to accelerate student learning, potentially contradicting Piaget’s notion of developmental stages. Teachers should regularly assess students’ understanding to identify areas where they need more support or challenge.

- Assessment Focus: The emphasis on standardized testing can shift the focus from process-oriented learning (as Piaget advocated) to outcome-based teaching. Educators should use assessments that reflect real-world tasks and allow students to demonstrate their understanding in multiple ways.

- Parental Expectations: Some parents may have misconceptions about play-based learning, believing it to be less rigorous than traditional instruction. Educators may need to address these concerns and communicate the value of play.

- Parental Involvement: Involving parents in understanding Piaget’s theory can foster consistency between home and school environments. Providing resources and information to parents about child development can empower them to support their child’s learning at home.

Other challenges

- Individual Differences: Piaget emphasized individual differences in cognitive development, but classrooms often have diverse learners. Meeting the needs of all students while maintaining a play-based approach can be demanding.

- Time Constraints: In some educational settings, there may be pressure to cover specific content or prepare students for standardized tests. Prioritizing play-based learning within these constraints can be difficult.

- Cultural Sensitivity: Recognizing and respecting cultural differences is essential. Piaget’s theory may need to be adapted to fit the specific cultural context of the children being taught.

Can Piaget’s Ideas Be Applied to Children with Special Educational Needs and Disabilities?

Yes, Piaget’s ideas can be adapted to support children with special educational needs and disabilities (SEND), though with important considerations:

- Individualized Approach : Tailor learning experiences to each child’s unique strengths, needs, and interests, recognizing that development may not follow typical patterns or timelines (Daniels & Diack, 1977).

- Concrete Learning Experiences : Provide hands-on, multisensory activities to support concept exploration, particularly beneficial for children with learning difficulties or sensory impairments (Lee & Zentall, 2012).

- Gradual Scaffolding : Break down tasks into manageable steps and provide appropriate support to help children progress through developmental stages at their own pace (Morra & Borella, 2015).

- Flexible Assessment : Modify Piagetian tasks to accommodate different abilities and communication methods, using multiple assessment approaches.

- Strengths-Based Focus : Emphasize children’s capabilities rather than deficits, using Piaget’s concepts to identify and build upon existing cognitive strengths.

- Interdisciplinary Approach : Combine Piagetian insights with specialized knowledge from fields like occupational therapy and speech-language pathology.

While Piaget’s theory offers valuable insights, it should be part of a broader, evidence-based approach that recognizes the diverse factors influencing development in children with SEND.

Social Media (Digital Learning)

Jean Piaget could not have anticipated the expansive digital age we now live in.

Today, knowledge dissemination and creation are democratized by the Internet, with platforms like blogs, wikis, social media, and generative AI allowing for vast collaboration and shared knowledge. This development has prompted a reimagining of the future of education.

Classrooms, traditionally seen as primary sites of learning, are being overshadowed by the rise of mobile technologies and platforms like MOOCs (Passey, 2013).

The millennial generation, the first to grow up with cable TV, the internet, and cell phones, relies heavily on technology.

They view it as an integral part of their identity, with most using it extensively in their daily lives, from keeping in touch with loved ones to consuming news and entertainment (Nielsen, 2014).

Social media platforms offer a dynamic environment conducive to Piaget’s principles. These platforms allow interactions that nurture knowledge evolution through cognitive processes like assimilation and accommodation.

They emphasize communal interaction and shared activity, fostering both cognitive and socio-cultural constructivism. This shared activity promotes understanding and exploration beyond individual perspectives, enhancing social-emotional learning (Gehlbach, 2010).

A standout advantage of social media in an educational context is its capacity to extend beyond traditional classroom confines. As the material indicates, these platforms can foster more inclusive learning, bridging diverse learner groups.

This inclusivity can equalize learning opportunities, potentially diminishing biases based on factors like race or socio-economic status, resonating with Kegan’s (1982) concept of “recruitability.”

However, there are challenges. While social media’s potential in learning is vast, its practical application necessitates intention and guidance. Cuban, Kirkpatrick, and Peck (2001) note that certain educators and students are hesitant about integrating social media into educational contexts.

This hesitancy can stem from technological complexities or potential distractions. Yet, when harnessed effectively, social media can provide a rich environment for collaborative learning and interpersonal development, fostering a deeper understanding of content.

In essence, the rise of social media aligns seamlessly with constructivist philosophies. Social media platforms act as tools for everyday cognition, merging daily social interactions with the academic world, and providing avenues for diverse, interactive, and engaging learning experiences.

Weaknesses of Piaget’s theory include:

Criticisms of research methods.

Some critics argue that Piaget’s clinical method lacked standardization and objectivity, making it difficult to replicate findings and generalize results.

The open-ended nature of questioning, while allowing for flexibility, also introduced potential biases from the researcher’s interpretations.

Additionally, the focus on verbal explanations may have underestimated the cognitive abilities of younger children or those with limited language skills.

- Small sample size : Piaget often used small, non-representative samples, frequently including only his own children or those from similar backgrounds (European children from families of high socio-economic status). This limits the generalizability of his findings (Lourenço & Machado, 1996).

The lack of inter-rater reliability and potential issues with clinical interviews (e.g., children misunderstanding questions or trying to please the experimenter) may have led to biased or inaccurate conclusions.

Using multiple researchers and more standardized methods could have improved reliability (Donaldson, 1978).

- Age-related issues : Some critics argue that Piaget underestimated the cognitive abilities of younger children. This may be due to the complex language used in his tasks, which could have masked children’s true understanding.

- Cultural limitations : Piaget’s research was primarily conducted with Western, educated children from relatively affluent backgrounds. This raises questions about the universality of his developmental stages across different cultures (Rogoff, 2003).

Challenges to Key Concepts and Theories

Fixed developmental stages.

Piaget’s concept of fixed developmental stages has been challenged by other theorists and researchers.

Vygotsky and Bruner would rather not talk about stages at all, preferring to see development as a continuous process.

Others have queried the age ranges of the stages. Some studies have shown that progress to the formal operational stage is not guaranteed.

For example, Keating (1979) reported that 40-60% of college students fail at formal operational tasks, and Dasen (1994) states that only one-third of adults ever reach the formal operational stage.

Current developmental psychology has moved beyond seeing development as progressing through discrete, universal stages (as Piaget proposed) to view it as a more gradual, variable process influenced by social, genetic, and cultural factors.

Current perspectives acknowledge greater variability in the timing and sequence of developmental milestones.

There’s greater recognition of the brain’s plasticity and the potential for cognitive growth throughout the lifespan.

This challenges the idea of fixed developmental endpoints proposed in stage theories.

Cultural and individual differences

Cultural differences in cognitive development challenge the universality of Piaget’s stages

The fact that the formal operational stage is not reached in all cultures and not all individuals within cultures suggests that it might not be biologically based.

- According to Piaget, the rate of cognitive development cannot be accelerated as it is based on biological processes however, direct tuition can speed up the development which suggests that it is not entirely based on biological factors.

- Because Piaget concentrated on the universal stages of cognitive development and biological maturation he failed to consider the effect that the social setting and culture may have on cognitive development.

Cross-cultural studies show that the stages of development (except the formal operational stage) occur in the same order in all cultures suggesting that cognitive development is a product of a biological maturation process.

However, the age at which the stages are reached varies between cultures and individuals which suggests that social and cultural factors and individual differences influence cognitive development.

Dasen (1994) cites studies he conducted in remote parts of the central Australian desert with 8—to 14-year-old Indigenous Australians.

He gave them conservation of liquid tasks and spatial awareness tasks. He found that the ability to conserve came later in the Aboriginal children, between the ages of 10 and 13 (as opposed to between 5 and 7, with Piaget’s Swiss sample).

However, he found that spatial awareness abilities developed earlier among Aboriginal children than among Swiss children.

Such a study demonstrates that cognitive development is not purely dependent on maturation but on cultural factors as well—spatial awareness is crucial for nomadic groups of people.

Underemphasis on social and emotional factors

While Piaget’s theory focuses primarily on individual cognitive development, it arguably underestimates the crucial role of social and emotional factors.

Lev Vygotsky , a contemporary of Piaget, emphasized the social nature of learning in his sociocultural theory.

Vygotsky argued that cognitive development occurs through social interactions, particularly with more knowledgeable others (MKOs) such as parents, teachers, or skilled peers.

He introduced the concept of the Zone of Proximal Development ( ZPD ), which represents the gap between what a child can do independently and what they can achieve with guidance.

Furthermore, Vygotsky viewed language as fundamental to thought development, asserting that social dialogue becomes internalized as inner speech, driving cognitive processes. This perspective highlights how cultural tools, especially language, shape thinking.

Emotional factors, including motivation, self-esteem, and relationships, also play significant roles in learning and development – aspects not thoroughly addressed in Piaget’s cognitive-focused theory.

This social-emotional dimension of development has gained increasing recognition in modern educational and developmental psychology.

Underestimating children’s abilities

Critics argue that Piaget may have underestimated children’s cognitive abilities due to methodological issues.

Piaget failed to distinguish between competence (what a child can do) and performance (what a child can show when given a particular task).

When tasks were altered, performance (and therefore competence) was affected. Therefore, Piaget might have underestimated children’s cognitive abilities.

For example, a child might have object permanence (competence) but still be unable to search for objects (performance). When Piaget hid objects from babies, he found that it wasn’t until after nine months that they looked for them.

However, Piaget relied on manual search methods – whether the child was looking for the object or not.

Later, researchers such as Baillargeon and Devos (1991) reported that infants as young as four months looked longer at a moving carrot that didn’t do what it expected, suggesting they had some sense of permanence, otherwise they wouldn’t have had any expectation of what it should or shouldn’t do.

Jean Piaget’s Legacy and Ongoing Influence

Piaget’s ideas on developmental psychology have had an enormous influence. He changed how people viewed the child’s world and their methods of studying children.

He inspired many who followed and took up his ideas. Piaget’s theories inspired extensive research in the field of cognitive development.

Theoretical Contributions

- Seminal Theory : Piaget (1936) was one of the first psychologists to study cognitive development systematically. His contributions include a stage theory of child cognitive development, detailed observational studies of cognition in children, and a series of simple but ingenious tests to reveal different cognitive abilities.

- Neo-Piagetian theories : Researchers have built upon Piaget’s stage theory of cognitive development, incorporating information processing and brain development to explain cognitive growth, emphasizing individual differences and more gradual developmental progressions (Case, 1985; Fischer, 1980; Pascual-Leone, 1970).

His emphasis on qualitative, exploratory research, as opposed to strictly quantitative measures, opened new avenues for studying children’s cognitive development and challenged prevailing assumptions about their capabilities.

Impact on Educational Practices

Early Childhood Education : Piaget’s theories underpin many early childhood programs that emphasize play-based learning, sensory experiences, and exploration.

Constructivist Pedagogy: Piaget’s idea that children construct knowledge through interaction with their environment led to a shift from teacher-centered to child-centered approaches. This emphasizes exploration, discovery, and hands-on activities.

By understanding Piaget’s stages, educators can create environments and activities that challenge children appropriately.

The National Association for the Education of Young Children ( NAEYC ) has incorporated Piagetian principles into its DAP framework, influencing early childhood education policies worldwide.

Parenting Practices

Piaget’s theory influenced parenting by emphasizing stimulating environments, play, and supporting children’s curiosity.

Parents can use Piaget’s stages to have realistic developmental expectations of their children’s behavior and cognitive capabilities.

For instance, understanding that a toddler is in the pre-operational stage can help parents be patient when the child is egocentric.

Play Activities

Recognizing the importance of play in cognitive development, many parents provide toys and games suited for their child’s developmental stage.

Parents can offer activities that are slightly beyond their child’s current abilities, leveraging Vygotsky’s concept of the “ Zone of Proximal Development ,” which complements Piaget’s ideas.

- Peek-a-boo : Helps with object permanence.

- Texture Touch : Provide different textured materials (soft, rough, bumpy, smooth) for babies to touch and feel.

- Sound Bottles : Fill small bottles with different items like rice, beans, bells, and have children shake and listen to the different sounds.

- Memory Games : Using cards with pictures, place them face down, and ask students to find matching pairs.

- Role Playing and Pretend Play : Let children act out roles or stories that enhance symbolic thinking. Encourage symbolic play with dress-up clothes, playsets, or toy cash registers. Provide prompts or scenarios to extend their imagination.

- Story Sequencing : Give children cards with parts of a story and have them arranged in the correct order.

- Number Line Jumps : Create a number line on the floor with tape. Ask students to jump to the correct answer for math problems.

- Classification Games : Provide a mix of objects and ask students to classify them based on different criteria (e.g., color, size, shape).

- Logical Puzzle Games : Games that involve problem-solving using logic, such as simple Sudoku puzzles or logic grid puzzles.

- Debate and Discussion : Provide a topic and let students debate the pros and cons. This promotes abstract thinking and logical reasoning.

- Hypothesis Testing Games : Present a scenario and have students come up with hypotheses and ways to test them.

- Strategy Board Games : Games like chess, checkers, or Settlers of Catan can help in developing strategic and forward-thinking skills.

Comparing Jean Piaget’s Ideas with Other Theorists

Integrating diverse theories enables early years professionals to develop a comprehensive view of child development.

This allows for creating holistic learning experiences that support cognitive, social, and emotional growth.

By recognizing various developmental factors, professionals can tailor their practices to each child’s unique needs and background.

Comparison with Lev Vygotsky

Differences:.

Vygotsky argues that children learn through social interactions, building knowledge by learning from more knowledgeable others, such as peers and adults.

In other words, Vygotsky believed that culture affects cognitive development.

- Stage-Based vs Continuous Development : Piaget proposed a stage-based model of cognitive development, while Vygotsky viewed development as a continuous process influenced by social and cultural factors.

Vygotsky argues that the development of language and thought go together and that the origin of reasoning has more to do with our ability to communicate with others than with our interaction with the material world.

Alternatively, Vygotsky would recommend that teachers assist the child to progress through the zone of proximal development by using scaffolding.

Similarities:

- Both theories view children as actively constructing their own knowledge of the world; they are not seen as just passively absorbing knowledge.

- They also agree that cognitive development involves qualitative changes in thinking, not only a matter of learning more things.

Comparison with Erik Erikson

Erikson’s (1958) psychosocial theory outlines 8 stages of psychosocial development from infancy to late adulthood.

At each stage, individuals face a conflict between two opposing states that shapes personality. Successfully resolving conflicts leads to virtues like hope, will, purpose, and integrity. Failure leads to outcomes like mistrust, guilt, role confusion, and despair.

- Cognitive vs. Psychosocial Focus : Piaget focuses on cognitive development and how children construct knowledge. Erikson emphasizes psychosocial development, exploring how social interactions shape personality and identity.

- Universal Stages vs. Cultural Influence : Piaget proposed universal cognitive stages relatively independent of culture. Erikson’s psychosocial stages, while sequential, acknowledge significant cultural influence on their expression and timing.

- Role of Conflict : Piaget sees cognitive conflict (disequilibrium) as a driver for learning. Erikson views psychosocial crises as essential for personal growth and identity formation.

- Scope of Development : Piaget’s theory primarily covers childhood to adolescence. Erikson’s theory spans the entire lifespan, from infancy to late adulthood.

- Learning Process vs. Identity Formation : Piaget emphasizes how children learn and understand the world. Erikson focuses on how individuals develop their sense of self and place in society through resolving psychosocial conflicts.

- Stage-based theories : Both propose that development occurs in distinct stages (Gilleard & Higgs, 2016).

- Age-related progression : Stages are generally associated with specific age ranges.

- Cumulative development : Each stage builds upon the previous ones.

- Focus on childhood : Both emphasize the importance of early life experiences.

- Active role of the individual : Both see children as active participants in their development.

Comparison with Urie Bronfenbrenner

Bronfenbrenner’s (1979) ecological systems theory posits that an individual’s development is influenced by a series of interconnected environmental systems, ranging from the immediate surroundings (e.g., family) to broad societal structures (e.g., culture).

Bronfenbrenner’s theory offers a more comprehensive view of the multiple influences on a child’s development, complementing Piaget’s focus on cognitive processes with a broader ecological perspective.

- Individual vs. Ecological Emphasis : Piaget focuses on individual cognitive development through independent exploration. Bronfenbrenner emphasizes the complex interplay between an individual and multiple environmental systems, from immediate family to broader societal influences.

- Stage-based vs. Systems Approach : Piaget proposed distinct stages of cognitive development. Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory views development as ongoing interactions between the individual and various environmental contexts throughout the lifespan.

- Role of Environment : For Piaget, the environment provides opportunities for cognitive conflict and schema development. Bronfenbrenner sees the environment as a nested set of systems ( microsystem , mesosystem , exosystem , macrosystem , chronosystem ) that directly and indirectly influence development.

- Cognitive Structures vs. Proximal Processes : Piaget focused on the development of cognitive structures (schemas). Bronfenbrenner emphasized proximal processes – regular, enduring interactions between the individual and their immediate environment – as key drivers of development.

- Discovery Learning vs. Contextual Learning : Piaget advocated for discovery learning to challenge existing schemas. Bronfenbrenner would emphasize the importance of understanding and leveraging the various ecological contexts in which learning occurs, from family to cultural systems.

- Both recognize the child as an active participant in development.

- Both acknowledge the importance of the child’s environment in shaping development.

What is cognitive development?

Cognitive development is how a person’s ability to think, learn, remember, problem-solve, and make decisions changes over time.

This includes the growth and maturation of the brain, as well as the acquisition and refinement of various mental skills and abilities.

Cognitive development is a major aspect of human development, and both genetic and environmental factors heavily influence it. Key domains of cognitive development include attention, memory, language skills, logical reasoning, and problem-solving.

Various theories, such as those proposed by Jean Piaget and Lev Vygotsky, provide different perspectives on how this complex process unfolds from infancy through adulthood.

What are the 4 stages of Piaget’s theory?

Piaget divided children’s cognitive development into four stages; each of the stages represents a new way of thinking and understanding the world.

He called them (1) sensorimotor intelligence , (2) preoperational thinking , (3) concrete operational thinking , and (4) formal operational thinking . Each stage is correlated with an age period of childhood, but only approximately.

According to Piaget, intellectual development takes place through stages that occur in a fixed order and which are universal (all children pass through these stages regardless of social or cultural background).

Development can only occur when the brain has matured to a point of “readiness”.

What are some of the weaknesses of Piaget’s theory?

However, the age at which the stages are reached varies between cultures and individuals, suggesting that social and cultural factors and individual differences influence cognitive development.

What are Piaget’s concepts of schemas?

Schemas are mental structures that contain all of the information relating to one aspect of the world around us.

According to Piaget, we are born with a few primitive schemas, such as sucking, which give us the means to interact with the world.

These are physical, but as the child develops, they become mental schemas. These schemas become more complex with experience.

According to Piaget, how does a child’s verbal thought relate to their active and concrete thought?

Piaget acknowledged the complex relationship between a child’s verbal expressions and their active engagement with the concrete world.

He recognized that children, like adults, possess a layer of “purely verbal thought” that can be superimposed over their “active and concrete thought”.

This verbal layer can manifest in various ways, including:

Inventing Stories : Piaget observed that children frequently invent stories, both during questioning and in their everyday lives.

He argued that these stories offer insights into the child’s thought processes, as they often reflect the child’s understanding of causality, relationships, and the workings of the world

Responding to Hypothetical Scenarios: In his studies on moral judgment, Piaget used hypothetical dilemmas to explore children’s reasoning.

He recognized that these verbal scenarios, while not directly mirroring the child’s lived experience, could still elicit valuable insights into their moral reasoning processes.

However, Piaget also expressed concerns about the limitations of relying solely on verbal expressions to understand children’s thinking.

Verbal Thought as a Potential Distraction: Piaget cautioned that focusing too heavily on a child’s verbalizations might lead researchers away from observing their active engagement with the world, which he considered a crucial aspect of their cognitive development.

He emphasized the need to balance verbal inquiry with observations of the child’s actions and manipulations of physical objects.

The Risk of Misinterpreting Verbal Responses: Piaget emphasized that children’s verbal expressions could be influenced by various factors, such as a desire to please the interviewer or a misunderstanding of the question.

He stressed the importance of careful interpretation and the need to distinguish between “liberated” or “spontaneous” responses and those that are influenced by suggestion or other external factors.

To address these challenges, Piaget advocated for integrating verbal inquiry with observations of the child’s active and concrete engagement with the world:

Combining Verbal and Concrete Tasks: As his clinical method evolved, Piaget increasingly incorporated concrete tasks and manipulations into his research protocols.

By engaging children in activities that involved interacting with physical objects, he believed he could gain a more comprehensive understanding of their reasoning processes.

This shift is exemplified in his research on physical causality, where he presented children with concrete demonstrations, such as dropping a pebble into a glass of water, and then questioned them about their observations and explanations.

Using Language Rooted in the Child’s Experience: Piaget emphasized the importance of using language and concepts that were familiar to the child and connected to their concrete experiences.

He believed that this approach helped to ensure that the child understood the question and that their responses reflected their genuine thinking.

Ultimately, Piaget saw the relationship between verbal and concrete thought as a dynamic interplay that evolves as the child develops.

He believed that by carefully attending to both aspects of a child’s thinking, researchers could gain valuable insights into the complex processes of cognitive development.

- Baillargeon, R., & DeVos, J. (1991). Object permanence in young infants: Further evidence . Child development , 1227-1246.

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Harvard University Press.

- Bruner, J. S. (1966). Toward a theory of instruction. Cambridge, Mass.: Belkapp Press.

- Case, R. (1985). Intellectual development: Birth to adulthood. Academic Press.

- Central Advisory Council for Education, England (1967). Children and their primary schools [Plowden Report]. London: HMSO. Available at https://education-uk.org/documents/plowden/

- Cuban, L., Kirkpatrick, H., & Peck, C. (2001). High access and low use of technologies in high school classrooms: Explaining an apparent paradox. American Educational Research Journal , 38 (4), 813-834.

- Daniels, H., & Diack, H. (1977). Piagetian tests for the primary school . Routledge and Kegan Paul.

- Dasen, P. (1994). Culture and cognitive development from a Piagetian perspective. In W .J. Lonner & R.S. Malpass (Eds.), Psychology and culture (pp. 145–149). Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon.

- Donaldson, M. (1978) . Children’s minds . Fontana Press.

- Fisher, K., Hirsh-Pasek, K., Golinkoff, R. M., Singer, D. G., & Berk, L. (2011). Playing around in school: Implications for learning and educational policy. In A. D. Pellegrini (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of the development of play (pp. 341-360). Oxford University Press.

- Erickson, E. H. (1958). Young man Luther: A study in psychoanalysis and history . New York: Norton.

- Gehlbach, H. (2010). The social side of school: Why teachers need social psychology. Educational Psychology Review , 22 , 349-362.

- Guy-Evans, O. (2024, January 17). Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory . Simply Psychology. https://www.simplypsychology.org/bronfenbrenner.html

- Hughes, M. (1975). Egocentrism in preschool children . Unpublished doctoral dissertation. Edinburgh University.

- Inhelder, B., & Piaget, J. (1958). The growth of logical thinking from childhood to adolescence . New York: Basic Books.

- Keating, D. (1979). Adolescent thinking. In J. Adelson (Ed.), Handbook of adolescent psychology (pp. 211-246). New York: Wiley.

- Kegan, R. (1982). The evolving self: Problem and process in human development . Harvard University Press.

- Lee, K., & Zentall, S. S. (2012). Psychostimulant and sensory stimulation interventions that target the reading and math deficits of students with ADHD. Journal of Attention Disorders, 16 (4), 308-329.

- Nielsen. 2014. “Millennials: Technology = Social Connection.” http://www.nielsen.com/content/corporate/us/en/insights/news/2014/millennials-technology-social-connecti on.html.

- Lourenço, O. (2012). Piaget and Vygotsky: Many resemblances, and a crucial difference. New Ideas in Psychology, 30 (3), 281-295.

- Lourenço, O., & Machado, A. (1996). In defense of Piaget’s theory: A reply to 10 common criticisms . Psychological Review, 103 (1), 143-164.

- Matusov, E., & Hayes, R. (2000). Sociocultural critique of Piaget and Vygotsky. New Ideas in Psychology , 18 (2-3), 215-239.

- Morra, S., & Borella, E. (2015). Working memory training: From metaphors to models. Frontiers in Psychology, 6 , 1097.

- McLeod, S. (2024, January 24). Vygotsky’s Theory Of Cognitive Development . Simply Psychology. https://www.simplypsychology.org/vygotsky.html

- McLeod, S. (2024, January 24). Piaget’s Sensorimotor Stage of Cognitive Development . Simply Psychology. https://www.simplypsychology.org/sensorimotor.html

- McLeod, S. (2024, January 24). Piaget’s Preoperational Stage (Ages 2-7) . Simply Psychology. https://www.simplypsychology.org/preoperational.html

- McLeod, S. (2024, January 24). The Concrete Operational Stage of Cognitive Development . Simply Psychology. https://www.simplypsychology.org/concrete-operational.html

- McLeod, S. (2024, January 24). Piaget’s Formal Operational Stage: Definition & Examples . Simply Psychology. https://www.simplypsychology.org/formal-operational.html

- McLeod, S. (2024, January 25). Erik Erikson’s Stages Of Psychosocial Development . Simply Psychology. https://www.simplypsychology.org/erik-erikson.html

- Mayer, S. J. (2005). The early evolution of Jean Piaget’s clinical method. History of Psychology, 8 (4), 362–382. https://doi.org/10.1037/1093-4510.8.4.362

- Ojose, B. (2008). Applying Piaget’s theory of cognitive development to mathematics instruction. The Mathematics Educator, 18 (1), 26-30.

- Pascual-Leone, J. (1970). A mathematical model for the transition rule in Piaget’s developmental stages. Acta Psychologica, 32 , 301-345.

- Passey, D. (2013). Inclusive technology enhanced learning: Overcoming cognitive, physical, emotional, and geographic challenges . Routledge.

- Piaget, J. (1932). The moral judgment of the child . London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Piaget, J. (1936). Origins of intelligence in the child. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Piaget, J. (1945). Play, dreams and imitation in childhood . London: Heinemann.

- Piaget, J. (1952). The child’s conception of number. Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Piaget, J. (1952). The origins of intelligence in children. (M. Cook, Trans.). W W Norton & Co. (Original work published 1936)

- Piaget, J. (1957). Construction of reality in the child. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Piaget, J., & Cook, M. T. (1952). The origins of intelligence in children . New York, NY: International University Press.

- Piaget, J. (1962). The language and thought of the child (3rd ed.). (M. Gabain, Trans.). Routledge & Kegan Paul. (Original work published 1923)

- Piaget, J. (1970). The Psychology of Intelligence . New York: Basic Books.

- Piaget, J. (1981). Intelligence and affectivity: Their relationship during child development. (Trans & Ed TA Brown & CE Kaegi) . Annual Reviews.

- Piaget, J. (1985). The equilibration of cognitive structures: The central problem of intellectual development. (T. Brown & K. J. Thampy, Trans.). University of Chicago Press. (Original work published 1975)

- Piaget, J., & Inhelder, B. (1956). The child’s conception of space. Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Piaget, J., & Szeminska, A. (1952). The child’s conception of number. Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Plowden, B. H. P. (1967). Children and their primary schools: A report (Research and Surveys). London, England: HM Stationery Office.

- Ratcliff, M. J. (2024). Jean Piaget and the autonomous disciples, Alina Szeminska and Bärbel Inhelder: From the “critical method” to the appropriation of research culture. History of Psychology, 27 (4), 317–332.

- Rogoff, B. (2003). The cultural nature of human development . Oxford University Press.

- Shayer, M. (1997). The Long-Term Effects of Cognitive Acceleration on Pupils’ School Achievement, November 1996.

- Siegler, R. S., DeLoache, J. S., & Eisenberg, N. (2003). How children develop . New York: Worth.

- Smith, L. (Ed.). (1996). Critical readings on Piaget . London: Routledge.

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Wadsworth, B. J. (2004). Piaget’s theory of cognitive and affective development: Foundations of constructivism . New York: Longman.

Further Reading

- BBC Radio Broadcast about the Three Mountains Study

- Piagetian stages: A critical review

- Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory

Jean Piaget and His Theory & Stages of Cognitive Development

One of the most popular theories of cognitive development was created by Jean Piaget, a Swiss psychologist who believed that cognitive growth occurred in stages. Piaget studied children through to their teens in an effort to determine how they developed logical thinking. He attempted to document the stages of cognitive development by observing the memory processes of children.

Essentially, Piaget believed that humans create their own understanding of the world. In theological terms, he was a psychological constructivist , believing that learning is caused by the blend of two processes: assimilation and accommodation. Children first reflect on their prior experiences to understand a new concept and then adjust their expectations to include the new experience. This means that children are continuously constructing knowledge based on the newly presented ideas, which lead to long-term changes. Piaget was more focused on the cognitive developments presented over time.

- Vygotsky’s Zone of Proximal Development and Scaffolding

- Lev Vygotsky – Sociocultural Theory of Cognitive Development

- Andragogy Theory – Malcolm Knowles

- Social Learning Theory: Albert Bandura

Through his studies, Piaget declared that cognitive development occurred in four stages throughout one’s childhood:

- Stages occur in order.

- Children did not skip stages but pass through each one.

- There are visible changes from one stage to the next.

- The stages occur as building blocks, each one using pieces from the last stage.

This type of developmental model incorporates each stage into the next, which is why it is often called a “staircase” model. On this staircase, Piaget labeled four stages of cognitive growth that occurred at an approximate age in children.

- Sensorimotor Intelligence, from birth to age 2.

- Preoperational Thinking, from ages 2 to 7.

- Concrete Operational Thinking, from ages 7 to 11.

- Formal Operational Thinking, from age 11 on.

The Sensorimotor Stage: Birth to Age 2

The first stage is aptly named after how infants learn until age two. From birth, infants absorb information through their senses: by touching, looking, and listening. They are very orally fixated and tend to put everything in their mouths. Piaget believed that this stage was valuable to their development, and each consecutive step is built on the growth that occurs in this stage.

We can observe the thought processes of infants through their actions. From about 6 months on, children begin to organize ideas into firm concepts that do not change. An infant may first not make sense of a specific toy, but as they begin to look at it, feel it, and manipulate it often, they are able to represent the object in their minds. This is how we can begin to observe knowledge in babies, as they begin to show understanding of an object for what it is. For example, by playing continuously with a toy animal, an infant begins to understand what the object is and recall their experiences associated with that toy. Piaget labeled this understanding as object permanence , which indicates the knowledge of the toy even if it is out of sight. He considered this understanding to be a major milestone in the sensorimotor stage and believed that it demonstrated the differences in the thought processes of toddlers compared to young infants.

The sensorimotor stage is unique in that is occurs without the use of language. As infants cannot speak, Piaget developed a few creative experiments in an effort to understand what they were thinking. His experiments were able to demonstrate that infants do represent objects and understand that they are permanent. In one of his experiments, Piaget consistently hid a toy underneath a blanket. Toddlers, or children between the ages of 18 and 24 months, took initiative to look for the toy themselves, but infants less than 6 months of age did not. The older infants interpreted the hiding of the toy as a prompt to search for it, which is thought to support the idea of object permanency.

The Preoperational Stage: Age 2 to 7

Children continue to build on the object representation that is significant to the sensorimotor stage in different activities. While the way they represent objects has no logic or reasoning behind it, they continue to grow in this area through dramatic play . Imaginative play, or the art of make-believe, is an indicative sign of this age and stage.

As dramatic play is considered to be beneficial to educational growth, teachers often promote its use in the classroom. The preoperational stage occurs from age two to age seven, which means that imaginative activities are encouraged from preschool all the way to second grade. Dramatic play is considered to be one of the first demonstrations of metacognition in children, or dual thinking. While engaged in imaginative play, children are simultaneously reflecting on the realistic experience.

The Concrete Operational Stage: Age 7 to 11

In Piaget’s next stage, children begin to represent objects and ideas in a more logical way. While the thought process is not on the same level as an adult, they begin to be more flexible in their thoughts and ideas. This allows them to solve problems in a more systematic way, leading to more success in educational activities in school. Piaget labeled this stage as concrete operational because he believed that children were able to manage concrete objects, but not yet think methodically about the representations of objects. It is only later that children are able to reflect on abstract events and manipulate representations of events. For example, a child may implement the rule “if nothing is added or taken away, then the amount of something stays the same.” Applying systemic rules or ideas may help a child solve simple tasks in the classroom, such as addition and subtraction problems or scientific calculations.

There are two things that distinguish concrete operational thinking from preoperational thinking. The first is reversibility , which allows a child to manipulate the order of any process. We can use the example of a sink or float science experiment to demonstrate the presence of reversibility. In this experiment, the child places various objects in a bucket of water, testing to see if they float or sink. A child in the preoperational stage would be able to describe the procedure taken, but only a child in the concrete operational stage would be able to retell the experiment in various ways, such as chronologically or out of order. Multi-step procedures are common in the classroom setting, which makes reversibility a valuable skill in learning. Children that are still in the preoperational stage may require assistance in activities in the form of prompts or reminders from the teacher. We can use the task of learning vocabulary from a story as an example in the classroom. The teacher may assign a multi-step instruction to the students: first, write down the words you don’t know as you come across them in the story, second, search for the definition before continuing on with the story, and third, have a friend quiz you on all of the words that you just learned. This type of multi-step instruction involves returning to the first and second tasks many times, which only children who have already reached the concrete operational stage are able to do.